One of the most famous events in England’s history was the Great Fire of London, which began on this day in 1666.

It was the perfect storm of conditions, politics and personalities that saw the inferno blaze for four days, unabated.

What happened in the Great Fire of London?

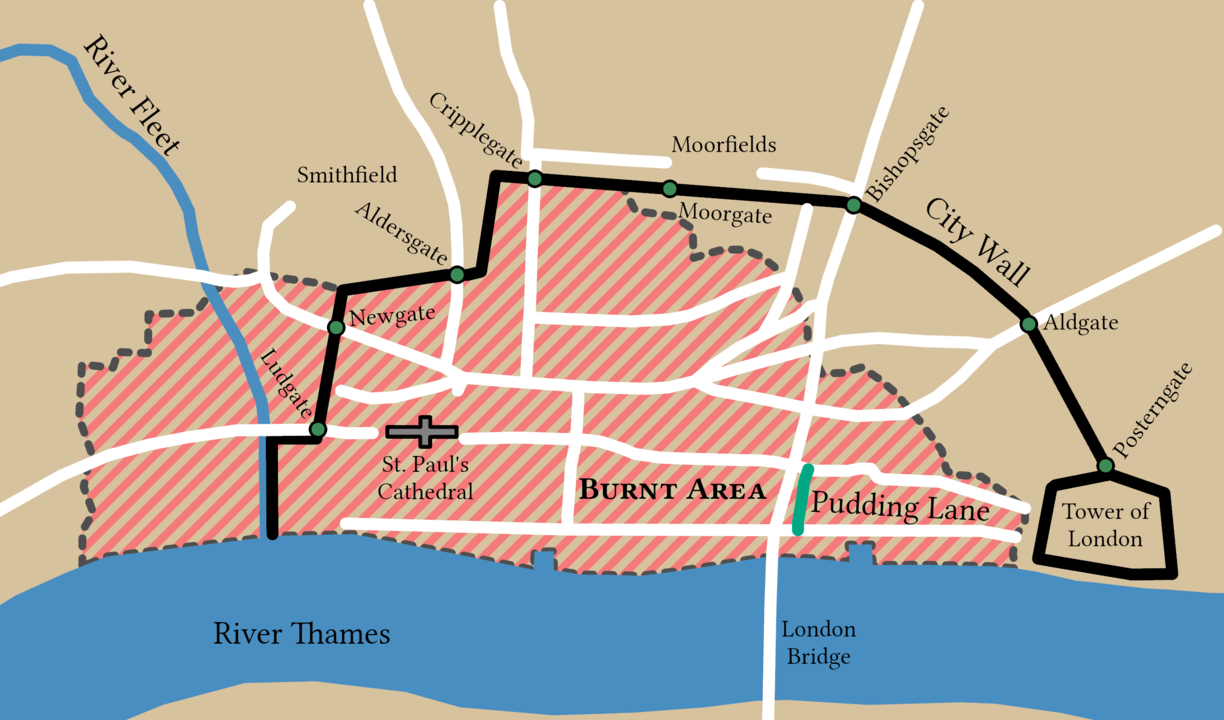

Day one – a spark in Pudding Lane

It was 2am on Sunday 2nd September when a workman smelled smoke coming from a local baker’s house.

The Farriner family who occupied the building were roused and fled from the upper floors of the house, across neighbouring roofs: the fire downstairs, which had begun probably an hour or so before, had made their exit impassable.

Their maid was too scared of the height to leave, and sadly became the first of a handful of casualties of the Great Fire.

Fire in the 17th century was a city's worst fear - given the narrow streets of close-knit timber-framed buildings, coupled with the commonplace use of candles and open fires at home.

By all accounts, London was a veritable rabbit warren of overcrowded, chaotic and unsanitary streets.

Flames could spread rapidly, an uncontrollable force of its own. Fire meant destruction to homes and businesses, costly repairs - and in many cases, death.

Such building practices had been banned for centuries in London, but the law was never properly enforced and the cost of brick was prohibitive for all but the upper level of society. ..

Day two – and the flames went higher…

A violent east wind fanned the flames and by dawn, London Bridge, just a few hundred metres from the bakery, was ablaze.

Thankfully, a gap on the bridge in the houses meant the fire could not spread south of the river, and repeat the tragedy of 30 years before. That fire had travelled to the opposite bank, significantly damaged the bridge and destroyed 42 properties, reaching Southwark, leaving a stretch of tinder-free bridge.

Diarist, courtier and Naval Office bureaucrat Samuel Pepys lived nearby, and walked to the Tower of London that Sunday morning. Having observed what was going on, he too was concerned by the blaze.

Being a known entity to the Monarch, he took a boat to Whitehall, informing the King and his brother James, Duke of York, of the situation and to urge action was taken.

Pepys suggested an idea to Charles II having shared the urgency of the situation, and being granted an audience: I ‘did tell the King and the Duke of York what I saw, and that unless his Majesty did command houses to be pulled down, nothing could stop the fire. They seemed much troubled, and the King commanded me to go to my Lord Mayor from him and command him to spare no houses but to pull down before the fire every way.’

Destruction of houses to create a fire break was a common tactic to contain a blaze, and with the winds still blowing from the east, the fire threatened the Palace of Westminster – the seat of government.

The sprawling Palace of Whitehall would follow if the blaze continued west.

Firefighting was performed by willing citizens and volunteers in the 17th century.

Parishes were supposed to keep buckets, axes, ladders and fire hooks (hooks on long poles) on hand to raze buildings and prevent spread of the flames

Usual tactics involved passing buckets of water from the Thames along a human chain to the fire, and pulling down buildings to stop flames spreading.

More rare tools that were not yet popular included fire squirts - effectively large one-man syringes that pumped a quantity of water out - and fire engines, which were barrels on wheels with handpumps and nozzles.

But Lord Mayor Bloodworth was unable to organise a group the size of needed to really fight the fire: Londoners ‘simply would not listen’ to his orders. He held supreme authority within the square mile, and not even the King could interfere.

Minute by minute, the fire grew stronger.

The fire began to create its own winds, turning into a firestorm that threw flames unpredictably, supported by strong gales around the city. There were reports of embers and sparks jumping 20 houses along.

At the end of the day, the fire had begun to travel against the wind and towards the stronghold of the Tower: Pepys began to pack up his house.

Panic spread as the conflagration continued to rage and turn both north and west during the night.

By Monday afternoon, smoke from the capital could be seen in Oxford, and Londoners began to leave their homes: the Thames was full of small vessels taking away families and their belongings by river, saving whatever they could carry from the fire, while others headed on foot, taking carts to carry their belongings.

Some headed the few miles north west to the hills of Hampstead and Highgate, but it was at Moorfields and Finsbury Hill – open field areas just beyond the city walls – that most Londoners fled.

The 18-foot-high Roman wall, which encircled the square mile, had helped keep London safe for centuries. There were seven gates, and the Thames that gave access to and from the capital.

But the river front was aflame, and many carts began to clog up the already-narrow paths out of London, it also posed a substantial risk: being shut in with the inferno.

Pepys wrote of the ordeal: I ‘walked, through the City, the streets full of nothing but people and horses and carts loaden with goods, ready to run over one another, and, removing goods from one burned house to another. They now removing out of Canning-streets [Cannon Street] (which received goods in the morning) into Lumbard-streets [Lombard Street], and further; and among others I now saw my little goldsmith, Stokes, receiving some friend’s goods, whose house itself was burned the day after.’

Read more > The causes and consequences of the Great Fire of London

The Duke of York secretly summoned soldiers from the surrounding counties to help fight the flames, and also to halt the looting which was taking place of residences in the area as occupants had fled.

Gracechurch Street was next to go up in flames, as did Lombard Street, where Pepys had seen people taking away their goods, and the Royal Exchange, with the flames continuing towards the wealthy area of Cheapside. This was a vital artery of the city sat just above St Paul’s Cathedral, which also housed most of the city’s shops and traders.

Day three – a city on the brink

It was now Tuesday 4th September, the day which saw the most destruction: the evening before, the fire was spreading down Watling Lane, in the direction of St Paul’s Cathedral.

The great medieval church was built in the time of William the Conqueror, and had stood at the heart of the capital for centuries, almost unchanged. Numerous Kings had lain in state at the cathedral following their deaths, but neither its history, nor its thick stone walls could save the cathedral.

King Charles II was seen helping to put the fire out with other men. He was personally involved in the firefighting, along with his brother, James.

With help from the volunteers from further afield plus Londoners that made up a fire brigade in the 17th century, the strategy was simple: tear down other buildings to make a break and stop the flames spreading, and put out what they could of the ongoing blaze.

They managed to contain the flames until late afternoon on Tuesday, when it jumped over the break at Mercers’ Hall – the headquarters of the merchants’ professional body – and began to consume Cheapside.

Pepys packed up his own house (which included burying his parmesan cheese and wine, of course), ready to leave.

‘Blowing up houses… stopped the fire when it was done, bringing down the houses in the same places they stood, and then it was easy to quench what little fire was in it,’ Pepys wrote of the strategy. He wanted to tear down the houses as the fire raged, making a smaller fire which was easier to quell. This was a typical tactic for the era, but the use of gunpowder carried its own risks.

By this point, however, it was clear the fire was out of control. Desperate times called for desperate measures.

Demolition seemed to ease the blaze in the east, but the prisons of Newgate and Ludgate were consumed (and prisoners moved elsewhere), with the destruction travelling along Fleet Street.

The King had sent troops to the edge of the city walls, where firebreaks were helping, still unable to override the Lord Mayor.

- St Paul’s Cathedral burning in the Great Fire (Wikimedia commons)

St Paul’s had caught fire by this point, ‘to which the scaffolds [for building repairs] contributed exceedingly,’ diarist John Evelyn noted.

The lead of the roof melted and then flowed down Ludgate Hill, such was the intensity of the heat. There are even reports of stones from the building exploding.

Day 4 – the battle is won

It was a brick wall at Middle Temple that stalled the spread on Wednesday morning (5th September).

Demolition continued apace to increase the break currently ahead of the flames. Together with a stroke of luck – the wind changed direction – the fire began blowing back onto itself, and south into the Thames.

There are some reports of a smattering of rain too, dampening potential tinder and stifling flames.

In the north of the square mile, Smithfield and Holborn were keeping the situation under control, if not winning.

Amazingly, just four deaths were reported as a direct result of the Great Fire of London. But subsequent fatalities – those trapped in demolished buildings, or without family or friends to notice their absence, victims of smoke inhalation – means that the toll is sadly probably a good deal higher… The consensus is that deaths would not have reached into the hundreds.

The destruction would cost London its Cathedral (St Paul’s), thousands of homes and approximately £10 million of damage – when the city’s income was just £12,000 per year.

The stats of the fire’s destruction

Stats vary as to the full extent of destruction but ranges put it between over half of the City being razed to the ground, up to 86% of it.

Approximately 13,200 houses, 84 of 109 churches and 44 livery company halls were ruined by the small spark that started in Pudding Lane, but turned into a four-day inferno.

Numbers vary wildly in relation to how many people were left homeless, but Vanessa Harding suggests the square mile’s population as being 100,000 in 1664.

The flames came close to reaching the Tower’s outer walls, which had stood as a bastion against danger for 600 years, as well as nearing Smithfield and almost to Temple Bar, before being extinguished.

London’s aftermath

Hysteria had raged throughout the ordeal, and Londoners looked for someone to blame. They looked to the foreigners of the city: the Catholics, Dutch, French. Or anyone who spoke poor English.

The situation was so dire that the Spanish Ambassador opened his home as a refuge to all foreigners, including the Protestant Dutch and the French.

The King attempted to quell this xenophobia, and addressed those who were made homeless in the fire. Charles II declared that the fire had not been started by foreign powers, but was act of God, which did nothing to soothe the people’s mood, and a scapegoat was found at the end of September…

With the people unconvinced by the King’s speech, and a genuine need for answers since Farriner maintained his innocence, a Parliamentary Committee was appointed to investigate the conflagration.

Conveniently, Robert Hubert, a French watchmaker, confessed to having started the fire in Pudding Lane as part of a team of 23 conspirators. While his story changed regularly, and it seems none of the judges believed he was responsible, Hubert was hanged at Tyburn for arson, to give a sense of closure to the disastrous chapter.

Thomas Farriner and his family even signed the bill accusing Hubert of starting the fire.

Naturally, disputes arose around topics like paying rent on destroyed buildings, and who was responsible for rebuilding. A special court – the Fire Court – was was created by Charles II to settle such legal matters.

A monument now stands near to where the bakery once did, marking the location the blaze began, designed by Robert Hooke with input from Christopher Wren. Built in the 1670s, it took until 1831 for an inscription blaming Catholics for the fire to be removed. The message had blamed ‘the treachery and malice of the Popish faction’.

It remains the world’s largest freestanding column.

Within a week after the fire had been quelled, Charles II was presented with new plans to rebuild the capital. Others followed soon after. Christopher Wren, John Evelyn, and Robert Hooke all attempted new ideas for the city’s design – but that did not include updating the street layout to make them more regular, meaning the structure remained higgeldy piggeldy, with many roads still narrow and crowded.

While rebuilding and repairs began quickly, it took nearly 50 years to fully rebuild the burnt area.

Sources

- Porter, S. (2011). The Great Fire of London. United Kingdom: History Press.

- Hanson, J. “Order and Structure in Urban Design: The Plans for the Rebuilding of London after the Great Fire of 1666.” Ekistics, vol. 56, no. 334/335, 1989, pp. 22–42. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43622101 . Accessed 31 Aug. 2025.

- Heyl, C. “A Miserable Sight: The Great Fire of London (1666).” Fiasko – Scheitern in Der Frühen Neuzeit: Beitraege Zur Kulturgeschichte Des Misserfolgs, edited by Stefan Brakensiek and Claudia Claridge, transcript Verlag, 2015, pp. 111–34. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv8d5t2b.8 . Accessed 31 Aug. 2025.

- Garrioch, D. “1666 and London’s Fire History: a Reevaluation.” The Historical Journal, vol. 59, no. 2, 2016, pp. 319–38. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24809852. Accessed 31 Aug. 2025.

- The Monument, History of The Monument, accessed 25 August 2025

- Britannica, The Great Fire of London, accessed 25 August 2025