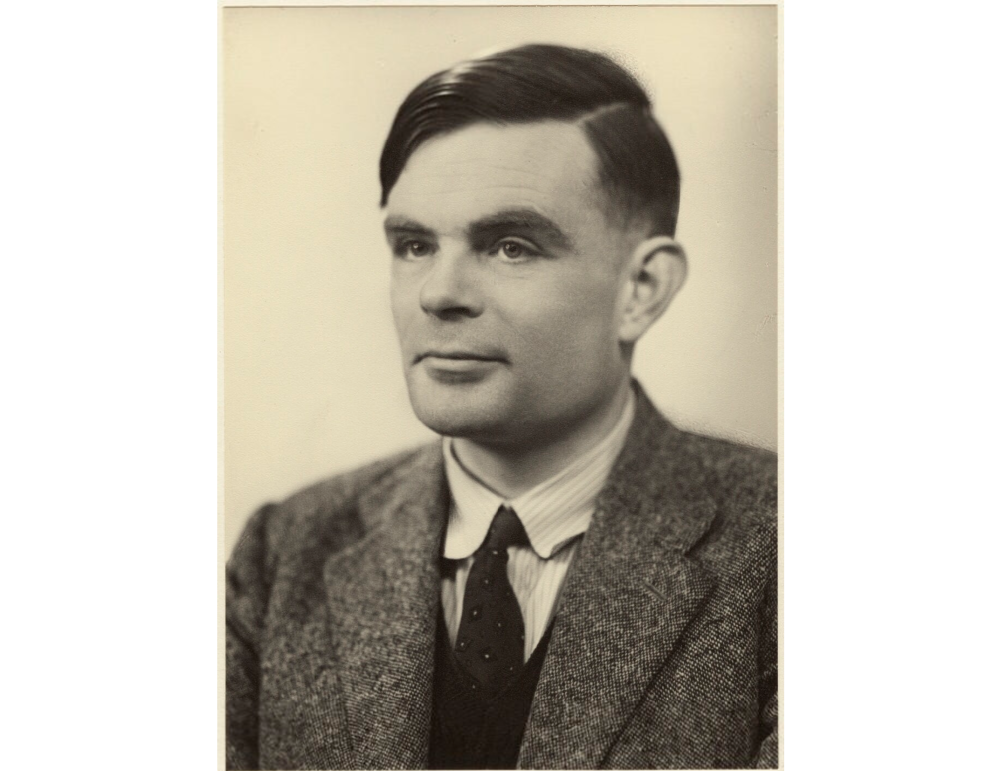

June is Pride Month, celebrating the LGBTQ+ community. A member of that group was Alan Turing, the man whose early computer helped crack the German Enigma code, shortening the Second World War by two years and saving thousands – perhaps millions – of lives.

Turing is generally considered to be the father of computer science and artificial intelligence, but his life tragically ended in suicide in 1954, after he was chemically castrated as punishment (instead of prison) for criminal gay acts.

Alan Mathieson Turing was born in Maida Vale, part of Paddington in London, to Julius and Ethel Turing (nee Stoney) in 1912. They had met in India, thanks to his career as a Civil Servant, and Ethel’s work as Chief Engineer at the Madras Railway, but they wanted their children to be raised in the UK and so returned home. Alan was the couple’s second child, after John.

Turing’s early education:

Aged six, Alan Turing was enrolled at St Michael’s, a day school in St Leonards-on-Sea. From a young age, his talent and aptitude for learning was recognised. He pursued chemistry as a passion project outside of the classroom. The headmistress at St Michael’s saw this, as did teachers at his next school – Hazelhurst Preparatory School.

Sherborne School in Dorset welcomed the youngster aged 13; Turing was so keen to attend his first day there, that in spite of the 1926 General Strike when only the milk floats ran, he cycled 60 miles from Southampton to the school alone, stopping overnight at an inn.

Such was the extraordinary nature of this journey, it was reported on in the local paper! But he had to begin school without his belongings until the strike was over (about another week) and he wrote of the difficulties this caused him in settling in to school life.

But Alan’s aptitude for maths and science did not impress many of his teachers; independent school Sherborne emphasised the classics – the humanities of English, History, Art, Philosophy and Languages. Biographer Andrew Hodges tells us that his headmaster wrote to his parents: “I hope he will not fall between two stools. If he is to stay at public school, he must aim at becoming educated. If he is to be solely a Scientific Specialist, he is wasting his time at a public school”.

His skill in the sciences could be seen in his ability to quickly grasp and deal with mathematical problems, sometimes without even having learnt the foundational theory that is usually necessary.

It was at Sherborne he got to know Christopher Morcom, the friend after which he named the machine that broke the Enigma code. Their friendship broke the loneliness that Alan experienced at school, possibly due to his lack of social skills.

They shared something of an intellectual companionship; Christopher and Alan conducted pet projects together. Turing’s biographer, Andrew Hodges, claims Morcom was his first love, referring to Alan’s writings of his friend. Alan wrote of wanting to ‘look again at his face’ as he felt attracted to him, and that he ‘worshipped the ground he trod on’. Christopher also ‘made everyone else seem so ordinary’.

Chris, as Alan would call him, contracted bovine tuberculosis after drinking infected cow’s milk, and sadly died from complications of the illness in 1930, aged just 17.

The event had a profound effect on Alan Turing. “I am sure I could not have found anywhere another companion so brilliant and yet so charming and unconceited,” Alan wrote of his friend.

“I regarded my interest in my work, and in such things as astronomy (to which he introduced me) as something to be shared with him and I think he felt a little the same about me.”

He did, however, keep in touch with Morcom’s mother, writing to her and remembering their friendship, committing himself to maths and science: “I know I must put as much energy if not as much interest into my work as if he [Christopher] were alive, because that is what he would like me to do,” Turing wrote.

Alan fondly remembered ‘the kind things he [Christopher] said to me’ and was impressed by his mathematical talents, which were ‘very thorough’. It seems this friendship and memory kept Alan interested and motivated to explore his subject further.

In 1931, Alan began his degree at King’s College, Cambridge, in Mathematics; he graduated in 1934 with first-class honours, and a year later became a fellow there, aged 22. His appointment was based on the strength of his dissertation, which proved the central limit theorem, a theory in probability. The theorem had – unbeknownst to Turing and those who assessed him – however, been proven in 1922 by a Finnish mathematician.

He received a Smith’s prize in 1936 for his work on probability theory, before Turing spent two years studying and working at Princeton. He received his PhD there in 1938.

Whilst in the US, Alan enjoyed cryptography, and spent time trying to build mathematical computers to solve problems.

It was at university that Turing’s sexuality became ‘a definitive part of his identity’. He took an occasional lover in fellow maths student, James Atkins, although he did not appear to mix with other gay men, who were generally found in the literary circle at King’s.

Bletchley Park – ‘Station X’:

Alan Turing joined the Government Code and Cypher School (GCCS) after the department realised they needed the assistance of mathematicians in order to solve this problem. Dillwyn ‘Dilly’ Knox, a senior GCCS codebreaker, was leading the group working on Enigma under Commander Alastair Denniston.

The school had recruited him from Cambridge, knowing of his Turing machine: a forerunner of the modern computer, able to perform calculations at astonishing speed.

Alan was allowed to take some of the information about Enigma back to King’s, probably because it made sense for the best minds – the reserve force to be used during the war – to have a grasp of the problem before the hostilities actually began.

At first GC&CS’s recruitment policy looked for ‘men of the Professor type’ through contacts at Oxford and Cambridge, before 1939. Gordon Welchman and Bill Tutte were found this way, while others like Dilly Knox and Nigel de Grey had started their codebreaking careers in the First World War.

Turing, 27 at the time, was hired to help Knox on a part-time basis in 1938, possibly on the recommendation of a senior academic who had worked for the government in a similar capacity during the First World War.

Alan Turing came in every few weeks or so, planning to take up a full time position when the war began, as it began to prove inevitable. The other recruit Alan worked with closely was Peter Twinn, 23, a physicist from Oxford University. Their work focused on analysing the cypher machine used by the Germans: Enigma.

The invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany in 1939, however, drew Britain into World War Two that September: the British Government had promised to defend Poland’s eastern borders, hoping to call the Germans’ bluff and prevent full-scale war. Alas, it did not.

There were only around 150 Bletchley staff at this point, but the group soon swelled in numbers, and it was on 4th September that Alan took up his own position full-time.

Alan worked alongside Knox, Welchman, Jeffries, and Twinn, working in two cottages in the stable yard at Bletchley Park, an estate that lay on the train line between Oxford and Cambridge, near Milton Keynes. Turing lived in a tiny village three miles north of Bletchley, cycling to his work each day.

The group eventually moved into the famous Hut 8 in 1940.

The maths behind Enigma:

The use of radio, or wireless, was necessary in war in order to share messages over long distances at speed. But there was no way to secure these lines, meaning anyone who found the channel or frequency could have access to these messages.

Enigma was the German solution to this. It was a cypher machine, of typewriter appearance, that performed alphabet substitutions, which would be used to produce coded messages. Each time a letter is typed on the keyboard, another letter of the alphabet is typed. These letter substitutions are not random, but are decided by a series of rotors, changed in their position each day to produce different results and ensure maximum security.

No letter could ever represent itself, but for each letter pressed, the rotors were moved, meaning the next letter, even if it were the same, would have enciphered a different letter. For example, the word ‘three’ could be enciphered as ‘qhriw’, giving no indication that there was a duplicate letter in the word.

Deciphering Enigma was a slow and difficult process, thanks to the immense possibilities this system offered: 150,000,000,000,000,000,000 combinations made it practically unbreakable. The team certainly had an uphill struggle.

In July 1939, the Polish Cipher Bureau gave the British and French the information they held on Enigma – its rotors, and their methods of decryption to intercept German messages. Their work, however, ‘relied on an insecure indicator procedure,’ that was likely to be altered by the Germans for security. The Germans began strengthening their system by changing the cipher every day that year, but this was further secured in May 1940.

Gordon Welchman, a fellow Cambridge mathematician, wrote in his 1982 book about this wartime work: “Hut 6 ‘Ultra’ would never have got off the ground if we had not learned from the Poles, in the nick of time, the details both of the German military version of the commercial Enigma machine, and of the operating procedures that were in use”.

‘Ultra’ was the code name for such intelligence work.

Turing and Knox, working in Hut 8, developed an improvement to the Polish workings; they used ‘crib-based decryption’ creating the bombe to help with these solutions, building on the Polish Bomba machine. The team, including Turing, had worked to improve the machine, which was built before the war to crack earlier versions of Enigma.

The new Turing-Welchman Bombe was perfected in 1940, which allowed them to intercept and decipher Luftwaffe communications, giving the Allies information on military plans.

The work was dull and repetitive, and each day, new cyphers were set, rendering almost all work from previous periods useless. But it was also the key to bringing down the fascist enemy.

Alan, of course, had to keep state secrets from his family. He had never much cared about his appearance, always appearing dishevelled, and didn’t much like shaving. This, whilst genuine, certainly helped him play up to the absent-minded academic ‘don’ character the family saw in him, to help hide his work.

The Hut 8 team was aided by mistakes made by German operators, enabling those working on the cryptanalysis of Luftwaffe messages, and the British captured key tables (codebooks) and a real Enigma machine from a German U-boat taken in May 1941 helped with significant breakthroughs in the quest to crack the code.

Before this information was obtained by the British, naval attacks had sunk 282,000 tons of shipping each month, between March and June 1941. By November, the team were able to reduce this number to 62,000 tons.

Turing, in creating his bombe machine, reportedly told his assistant that he was “building a brain”. The original Turing Machine showed that machines, when programmed to follow certain rules, could essentially make decisions like a human.

Once set in motion, the machine, nicknamed Christopher by Turing, would search through all possible Enigma rotor variations until the right combination was found.

The complex Enigma methods used in German Naval communications were cracked in 1941, then again in 1943 (after the Navy had introduced extra components to the system).

Specifying and creating the bombe was the first of five major advances that Turing made during the Second World War. One other was developing a statistical procedure named ‘Banburismus’ for a more efficient use of the bombe, since certain number patterns could be excluded.

Towards the end of the war, Alan also developed a portable and secure voice scrambler, named Delilah; it wasn’t however, used in time for the war but was key to British intelligence services in later years.

Relationship with Joan Clarke

By 1940, the work had moved to the famous ‘Hut 8’, which focused on the German Naval Engima. Alan worked closely with Joan Clarke here, who joined in June the same year, after her abilities were noticed by Gordon Welchman in her undergraduate Geometry class.

He and Joan became friendly in 1941, going to the cinema together, spending their days off in one another’s company, and relishing in shared hobbies. They soon fell into a pattern of behaviour that largely reflected a romantic relationship, and they became engaged.

Alan admitted his sexual preferences – ‘homosexual tendencies’ – to her, believing in honesty, also claiming they shouldn’t expect their marriage to work out because of it. She was reportedly ‘unfazed’ by the revelation, and the pair met one another’s families, continuing to work side by side. Alan even made sure their schedules in Hut 8 aligned, so they could be together.

But Turing decided that he could not go through with the marriage, deciding to end the engagement in August. They had taken their quarterly weeks’ holiday and gone to Portmadoc, Wales, and upon their return, Alan made the difficult decision to break up with Joan. He certainly loved her, and they had even discussed children, but did not think it fair, and quoted Oscar Wilde to her:

‘Yet each man kills the thing he loves

By each let this be heard.

Some do it with a bitter look,

Some with a flattering word.

The coward does it with a kiss,

The brave man with a sword!’

The Ballad of Reading Gaol, Oscar Wilde

Of course, this caused tensions within Hut 8, even if the engagement had been secret from most of their colleagues, it was clear something had gone on between the pair. They managed to remain friends, and Clarke was made deputy head of Hut 8 in 1944.

Joan was awarded an MBE for her work in 1946, and went on to have a family with another man in the 1950s. She continued to work for GCCS’s successor, GCHQ, for the rest of her career, as Alan pursued his academic route.

The post-war years

In 1945, Alan Turing was awarded an OBE for his wartime contributions, which were not publicly known until 1975, thanks to the State Secrets act. Just seven years later, however, his world was turned upside down when he was convicted of ‘acts of gross indecency’ under the 1885 statute, generally considered acts between men short of actual intercourse.

Aged 39, Alan began a relationship with Arnold Murray, 19. On 23rd January 1952, Turing’s house in Manchester was burgled and he reported the incident to the police, after Murray admitted knowing the culprit – it had been (what we would call today) a hate crime.

When speaking to officers during the investigation, Alan admitted to his relationship with Murray, and in conjunction with the burglar’s statement accusing the pair, both men were was arrested. The burglar was freed, since Turing’s crimes as a sexual offender, at the time, forfeited his protection under the law.

Homosexuality was illegal in the UK until 1967, having been established as a crime in 1533 during the reign of Henry VIII.

During the ensuing trial, his solicitor reserved his defence, not providing any evidence to the contrary or arguing against the charges. Alan eventually submitted a guilty plea on the advice of his brother and solicitor, and the sentences he faced could be time in prison (up to two years), or probation – with a catch: he would have to submit to hormone injections (a form of oestrogen) for one year, which were designed to ‘decrease libido’.

Many of those convicted around the same time served less than a six-moth sentence, and the fact that Turing was a first-time offender played in his favour, as did his charge: gross indecency, rather than the more serious buggery label.

Alan Turing continued to work throughout the entire process, presenting ideas and writing papers, much like he had during his time with GCSC.

He chose the latter course of action: he ‘choose thinking and sacrificed feeling’ describes Hodges – chemical castration to enable him to continue his enquiries. Due to the increase of the female hormone in Turing’s body, he was rendered impotent and even developed breast tissue.

His conviction meant his security clearance was revoked, which prevented him from continuing with his cryptographic consultancy, though Turing kept his university job, probably on the intervention of friends and senior colleagues. This criminal record also meant that the US denied Alan entry into the country.

Interestingly, however, Alan retained his OBE, which would have been forcibly returned had the War Office been involved; the office did the same of anyone convicted under the same act as Turing.

Turing’s tragic end

Alan Turing’s housekeeper found him dead on 8th June 1954, two years after his conviction. He was found lying on the floor, froth around his mouth and a bitten apple nearby. Cyanide had ended his life.

No note had been written, and no one close to Alan found any warning signs. In fact, many would argue he ‘wasn’t the type’ for suicide, which was the conclusion the inquest reached in June 1954.

His brother, John, attended the inquest, and decided against contesting the verdict, despite the evidence being limited; the press had been following Alan since his first trial, and this news geared up their interest in him and his life as a gay mathematician.

However, this was not a verdict his mother accepted, knowing his use of cyanide in various scientific techniques, like gold-plating, always warning her son to wash his hands.

Theatre tickets for future showings were found in Turing’s house, as well as a written acceptance for an invite to the Royal Society later that month. He had spoken to his neighbours, who were due to move out of the area, just a few days previous over dinner, promising to come and visit them, whilst pleased his new neighbours would be a young family. One of his closest friends, Robin Furbank, had stayed just a week before his death, and there was no hint at any psychological crisis or instability in Alan’s personality. They also planned to meet again in July.

It didn’t appear that Alan was ready to die.

But Alan created a new will in February 1954, naming friend Nick Furbank as his executor, over his brother, divvying up his assets – totalling £4603 – between his family members and close friends. A superannuation policy he had signed up to at the university provided a further £6742, which John Turing ensured was fully passed to their mother.

Alan Turing’s legacy

In August 2009, a petition was begun in the UK, asking the government to apologise to Turing for the punishment he was given, and received thousands of signatures. Gordon Brown, Prime Minister at the time, acknowledged the petition and called Turing’s treatment “appalling”.

Two of his mathematical research papers were declassified and publicly released by the government in 2012, marking what would have been Turing’s 100th birthday.

‘Paper on Statistics of Repetitions’ and ‘The Applications of Probability to Crypt’ are thought to have been written whilst he was at Bletchley Park, but had been kept at GCHQ for decades, ‘because of the ‘continuing sensitivity’ the papers, indicating just how much of an impact he had on cryptography and artificial intelligence in the 20th century.

In May 2012, a private member’s bill was put before the House of Lords to grant Turing a statutory pardon for the charges of gross indecency. Under the Royal Prerogative of Mercy by The Queen, Justice Secretary Chris Grayling requested a pardon for Alan and thousands of his fellow men convicted under the anti-gay laws.

This was granted in 2013, but is problematic for many, as it does not negate the guilt or criminal record initially dispensed, for something that in Britain today, is considered normal. The men were sadly victims of their sexually-conservative age, and Alan Turing was arguably the greatest loss.

Mark Carney, the Bank of England’s Governor, revealed in 2019 that Turing would feature on the new £50 note: “Turing is a giant on whose shoulders so many now stand”.

Alan Turing was chosen from a short list of 12 notable figures, after over 200,000 nominations for him.