The King has granted a PhD student access to the Royal Archives and Royal Collection to study the historic links between the Royal Family and the international slave trade.

Camilla de Koning is currently researching her thesis at University of Manchester, with the project co-sponsored by Historic Royal Palaces, the charity responsible for the upkeep of the Tower of London and Kensington Palace, amongst others.

She began working in October with ‘full access’ to both repositories, just a month after Charles’ accession – which indicates that this was originally a decision approved by the late Queen.

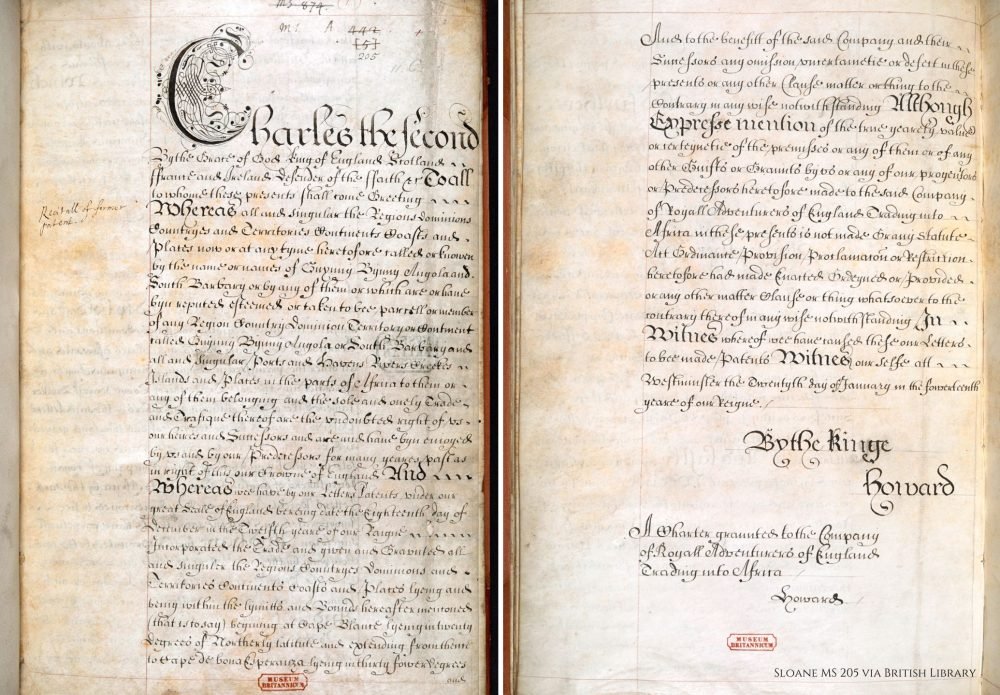

De Koning, a Dutch researcher, is beginning her review with the establishment of the Royal African Company in 1660 by Charles II and his brother, the Duke of York, future James II. Originally founded to exploit the gold fields up the Gambia River, it soon developed into leading a brutal and sustained slave trade.

In 1689, a transfer of £1,000 of shares (approx £203,000 today) in the Royal African Company was made from the company’s deputy governor, Edward Colston, to William III. The King himself was accompanied by 200 enslaved Africans from the Dutch colony of Surinam, when he arrived in England in the Glorious Revolution.

However, British links go back even further, with Elizabeth I sponsoring the first explorations – and exploitations – of the New World, although it is more opaque as to how the Hanoverian monarchs were involved.

A Buckingham Palace spokesperson said The King wants to continue his pledge to deepen his understanding of slavery’s impact with ‘vigour and determination’. ‘This is an issue that His Majesty takes profoundly seriously.’

‘Given the complexities of the issues it is important to explore them as thoroughly as possible,’ they added.

Last year, Charles attended the Barbadian independence handover ceremony, acknowledging the ‘the appalling atrocity of slavery’, which ‘forever stains our history’, and in Rwanda last year ‘I cannot describe the depths of my personal sorrow at the suffering of so many, as I continue to deepen my own understanding of slavery’s enduring impact.’

On Prince William’s visit to the Caribbean, he too recognised British links to Empire and commented that it was ‘for the people’ to decide, if they still wished to have the British Monarch as their own Head of State.

While Britain was an early adopter of the abolition of slavery (1807) – something for which Prince Albert campaigned on a global level – it continued in the wider empire until at least 1838 in some guise or other. Cities like, Glasgow, Liverpool and Bristol were largely built upon the fortunes of such trading, and London of course profited a great deal, too.

Britain was one of the most successful slave-trading countries, alongside Portugal; the two countries accounted for about 70% of all Africans transported to the Americas, according to the National Archives.

Britain was the most dominant actor between 1640 and 1807, and it is estimated that Britain transported 3.1 million Africans (of whom 2.7 million arrived, while 400,000 perished) to the British colonies in the Caribbean, North and South America and to other countries.

(British Library)

After the abolition, slave owners were compensation for their losses with £20 million of taxpayers’ money (approx £2 billion today); freed slaves were given nothing.

De Koning told BBC Radio 4’s World at One programme that ‘the royals are often overlooked when it comes to influence’, but were ‘actually very involved as diplomatic players’.

‘I’m hoping to change that perspective,’ she explained, ‘that you can see there are way more links between the colonial and the Monarch than ever have been investigated, or have ever been noticed, so we can flip that around.’

Her supervisor, Dr Edmond Smith, said the crown has ‘often been left out of discussions’ on the transatlantic slave trade, calling it an ‘important hole that needed to be filled through the research’.

In December, King Willem-Alexander of the Netherlands similarly commissioned research into the Dutch Royal Family’s role in slavery and colonialism.

De Koning’s research is expected to be complete in 2026. It remains unclear, however, how this research will then be acted upon, if at all, and also opens further discussion of such items like the Koh-I-Nor diamond, part of the Crown Jewels, and the spoils of war and plunder seen at the British Museum.