Royal palaces are complex machines that require a host of individuals, working diligently behind the scenes, to ensure all its operations run smoothly – from equerries to gardeners to maids to cooks.

Historic Royal Palaces’ new exhibition at Kensington Palace, ‘Untold Lives: A Palace at Work’, focuses on those who kept royal palaces afloat during the 17th and 18th centuries.

The exhibition features a range of items relating to Queen Charlotte. Visitors are treated to the only known surviving dress worn by the Consort to George III. The dress is not a typical fashion piece of the era, as it is made up entirely of lace, with hundreds of strips of bobbin lace pieced together. It also has small C’s on the dress for her initial.

at Kensington Palace, in ‘Untold Lives: A Palace at Work’

A new item in its collection is on show: an apron worn by Ann Elizabeth Thielcke, who was Queen Charlotte’s Wardrobe Maid in 1786. She was responsible for dressing the Queen every morning and would therefore have had direct access to her unlike other workers.

More often than not, fabrics and clothing were reused once past their best, so everyday clothing is a rare find. You might remember Elizabeth I’s dress being reused as an altar cloth, having been gifted to a close servant, then rediscovered centuries later. The apron gives visitors a fascinating insight into how they perceived working for the Royal Family, with the object being treasured for hundreds of years.

A third item that we liked, relating to Queen Charlotte, is a chair from her bedchamber suite. The chair was embroidered by Mrs Wright’s Royal School for Embroidering Females in the 1780s, and it displays the artistry and labour undertaken by orphaned young women taught at the school. The chair was personally commissioned by Queen Charlotte to support girls with limited options aside from domestic services.

The exhibition not only examines the working life of those who worked for the Royal Household but also the personal and more intimate aspects of their lives. Same-sex love and desire has always existed throughout history and evidence can be found throughout the centuries. At the time of Queen Charlotte’s life, same-sex love was seen as taboo, especially sex between women, while intercourse between men carried a death sentence until 1861.

The Offences Against the Person Act of this year meant the death penalty was abolished for acts of sodomy – but still was punishable by a minimum of 10 years imprisonment.

As part of the exhibition, there is a commissioned piece by Matt Smith, on the life of General Gustavus Guydickens, who was a Gentleman Usher in the court of Queen Charlotte from 1783. He was victim of the lawn, being accused of having sex with a younger man in Hyde Park near Kensington Palace.

Smith’s work takes the form of 12 meat platters, taking inspiration of Hogarth’s ‘The Rake’s Progress’ to piece together the life of Guydickens, to see how a key moment in an individual’s life could be seen as shameful and turned a life upside down. The surrounding quotes show how shame can affect a person’s life.

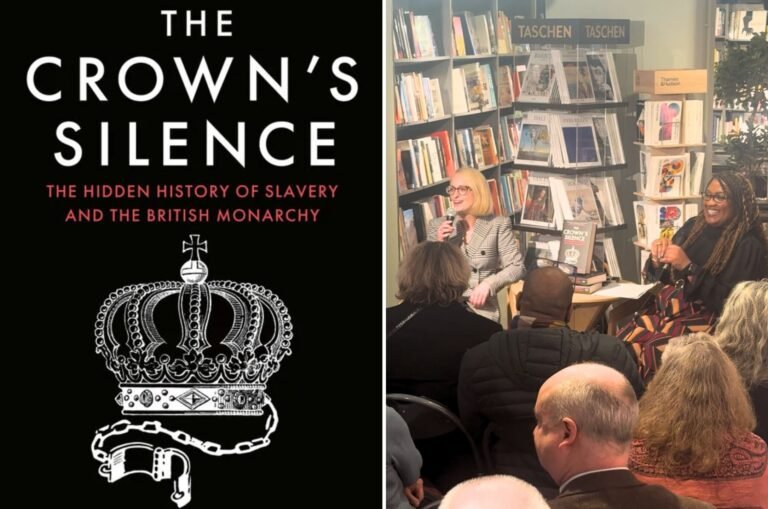

The exhibition also explores the links between slavery and the Royal Family, where some of those who worked in the royal household during the 17th and 18th Century arrived from the Caribbean, Africa and Asia, with Monarchs at the time being involved in the trade in enslaved people.

King Charles III has recently given permission for research to be done in the royal archives around these links.

As such, the exhibition features a new piece to Historic Royal Palaces’ collection – a painting lent by The King from the Royal Collection of William III, depicting the Stuart Monarch with a young Black attendant, holding William’s armour. It is not known whether the young individual is a real person who worked for William III, or if it is someone who was painted to reflect the King’s sources of wealth and overseas ambitions.

Also on display at the exhibition was the range of unusual roles undertaken by members of the Royal Household such as the ‘Groom of the Stool’ (who was responsible for looking after the Monarch on the toilet…!), to the rat-killer, and Frances Talbot’s role as ‘Keeper of Ice and Snow’.

Dr Mishka Sinha, exhibition co-curator at Historic Royal Palaces said: ‘With so little remaining of their presence, we often find that the legacy left behind of those who worked in the royal palaces 300 years ago is simply invisibility. By piecing together fragments of their history and presenting seemingly ordinary objects, we can build up a rich tapestry of unique stories of the real people behind the glamour of the court, whose hard physical labour and extraordinary skills ensured the protection and continuity of the royal household, palaces and objects that still exist today.

‘While there is still much research to do, instead of defining them by their job roles, this exhibition aims to tell the human stories of these people for the first time.’

Sebastian Edwards, exhibition co-curator at Historic Royal Palaces said: ‘The research into this exhibition has revealed a whole host of fascinating job roles and people who have kept the palaces running for centuries. From the keeper of ice and snow, to the rat catcher, their work has been crucial, but their stories remain largely untold, and we hope to now shine a light on them in our new exhibition.

‘In recognising the contribution they made, we hope that all our visitors find new connections with the Palace and their stories, celebrating the lasting legacy which their roles have contributed to these amazing historic places.’

You can see the exhibition as part of entry to Kensington Palace – book here.