William Adelin, son of Henry I, was one of those Princes and heirs whose reign was never to be. He died after his vessel, The White Ship, hit rocks as he sailed home to England. Here is his story…

The modern British Monarchy is a very stable thing. When in the fullness of time Queen Elizabeth II passes on her crown, we can fairly easily predict the order of succession for the next century, Charles, William and George, barring a freak accident or enormous national upheaval (neither of which seem likely).

But English history is littered with ‘almost rans’ and ‘nearly kings’, men and women who came near to the supreme power of the throne, but through illness, misfortune or chance encounter, were swept aside, out of the tide of history, and soon forgotten.

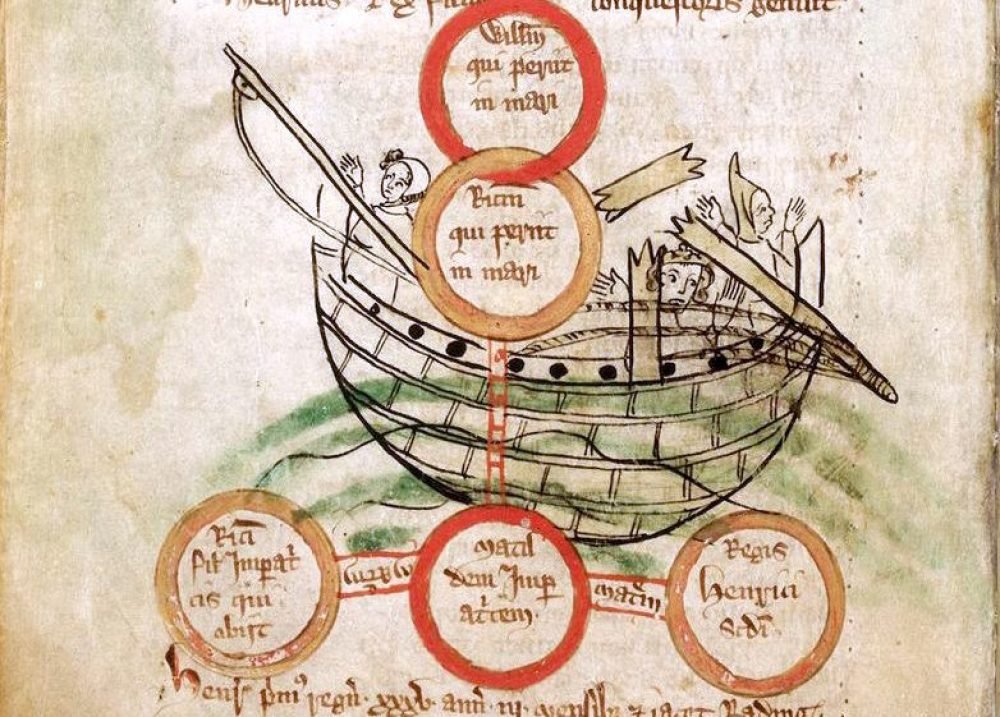

Perhaps the most brutal loss of a future King, and possibly the one whose loss weighed most heavily upon immediate English history, was William Adelin, only son of Henry I; his role in English history was abruptly ended on 25th November 1120 when he was drowned in the English Channel, while traveling aboard the so-called ‘White Ship’.

His father, Henry I, in common with our own Monarch, was not only King of England, but held other titles which came with the history of the conquest. Henry was also Duke of Normandy and as such, obliged to cross the Channel regularly; far-ranging travel, then as now, has always been a feature of Kingship. The King needed to see his people and to be seen by them, it was always necessary for him to calm restive frontiers and secure new ones, dispense royal justice and raise taxes from his often-resentful barons. Crossing the Channel was unavoidable in these circumstances.

By the standards of the time, Henry I was an energetic king and a successful one, holding together his joint realm for 35 years from 1100-1135. He also holds the unusual distinction of being England’s most fecund king, fathering at least 25 children! Unfortunately only one legitimate son made it to adulthood, and on these slender foundations lay England’s destiny.

His favourite child, and by far the most important from a dynastic point of view, was always William Adelin, his one legitimate son. Henry doted on him – a contemporary chronicler even described Prince William as a ‘pampered prince’ – though raised with ‘immense care’. He was also gradually trained and invested with political power by his father. From the age of 12, the barons of England swore allegiance to William Adelin jointly with his father, we then begin to see the young Prince’s seal on royal documents. From the age of 15 Henry appointed him regent of England during his frequent campaigns on the continent, where by all accounts he performed well.

Finally, in 1119, he was created Duke of Normandy by his father to further secure his status and secure the families traditional lands, William was well on his was to becoming another successful Norman monarch.

However, William represented far more than simply the next in the line of Norman kings: through his mother, Matilda he was also a great great-grandson of the Saxon King, Edmund Ironside, and grandson of Malcolm Canmore, King of Scots. The Prince personified the unification of the new ruling class and the old, and consequently the hopes and ambitions of both the Norman and Saxon inhabitants of Britain for the future.

His very sobriquet ‘Adelin’ was a Norman variant of the old Anglo-Saxon title of ‘Aetheling’, a designation given to him by William of Malmsbury, one of the key chroniclers of the time, to express his potential for reconciliation between Norman and Saxon with his accession.

Which brings us to the White Ship and the events of 1120. In that year Henry and his son travelled to Normandy to put down rebellion and invest 17-year-old William officially as Duke, a clear sign of intent for the future. Prince William was also betrothed to the daughter of the Count of Anjou, securing a restive frontier, creating an alliance, and opening the possibility of future heirs.

The White Ship was captained by Thomas FitzStephen, an experienced captain whose father had held the honour of sailing William the Conquerers’ flagship during the Norman Conquest of 1066; FitzStephen also boasted of both his ships’ speed and his crews’ skill. While the King had already made alternative travel arrangements, he gave permission for his heir and several of his illegitimate children, as well as various young nobles, to travel home on the White Ship.

Henry I was a pious King and his court known for its saintly atmosphere, which contrasted heavily with the irreverence of his predecessor, William II. Perhaps it was this which led the unsupervised noblemen, finding themselves let off the leash, to drink as much as they could. Whether it was indeed, as some chroniclers held, by the orders of Prince William that the crew and passengers were given an excessive amount of wine before sailing, or simply a feature of the freer atmosphere compared with the King’s ship, is impossible now to say. Several passengers disembarked before sailing, having over-indulged, and the priests who came to bless the ship retreated in the face of drunken catcalls; it was not a promising omen.

By the time the White Ship left port, it was dark, and the King’s ship was already on its journey. However the captain confidently asserted that his faster ship would easily beat the King’s, head start or no. Urged on by the revellers, the ship sped through the icy waters, only to strike submerged rocks within sight of the shore.

The ship quickly sank, drowning most aboard, their panicked cries floating over the waters to the town of Barfleur, but the townspeople could do nothing to help until dawn – by then it was far too late. It was later said that Prince William had managed to reach a life boat, but turned back upon hearing the cries of his half-sister. In a scene eerily reminiscent of that most infamous 20th century disaster, the Titanic, his boat was then overwhelmed by panicked and drowning people, and capsized, the Prince lost with it.

Only one passenger survived the night in the freezing ocean to tell the tale: a butcher, who had fortunately wrapped himself in skins before sailing. Later legend held that Captain FitzStephen survived, but upon surfacing and hearing of Prince William’s death from the butcher, disappeared back under the waves, unwilling to face the king.

Meanwhile back home in England, where the King himself had arrived safely, no one could bear to tell Henry I the news. Eventually, a young boy was persuaded to reveal the the awful truth by the Archbishop of Canterbury, upon which the King fell on his face, tore at his beard and wept uncontrollably with grief. The enormity of the loss of so promising a-Prince, and the potential instability this caused, flows from the chronicles. Henry of Huntingdon, a contemporary of the King, mourned the boy who ‘instead of wearing embroidered robes…floated naked in the waves, and instead of ascending a lofty throne…found his grave at the bottom of the sea’.

The loss of so many heirs to so many noble houses had devastating repercussions for the kingdom, quite aside from the loss of the King’s only legitimate son; over 300 were drowned all told, and the Royal Family was not alone in losing a promising heir.

The result was years of chaos on a national scale, including inheritance disputes and rising violence. Despite remarrying the next year, King Henry was unable to father another heir. This mean that when he died in 1135 with no direct male heir, 20 years of civil war between his daughter, who many barons could not accept due to her gender, and his nephew Stephen – who many others could not accept because this would mean setting aside the kings direct descendants – ensued. Known only as ‘The Anarchy’, the civil war devastated the country, with the Anglo-Saxon chronicle remembering it as a time when ‘Christ and his angels slept’.

We will never know what kind of King William Adelin could have made, or what sort of future England would have had under his rule. Given the attention paid to his upbringing by his astute father, the early responsibilities he discharged with skill and care, and the fact that King Henry still had many years to live and continue his education, we can imagine he would have been a successful one.

It would, however, have been an English future without Henry II, Richard the Lionheart, King John or indeed Magna Carta. Without Angevin mismanagement and empire building the future of the Anglo-Norman state could have evolved along radically different lines, and Prince Williams mixed heritage may have helped relations between Saxon and Norman improve to the point where a far less France centric culture emerged with time.

But for those living at the time, and in the decades following, the implications of his death were clear, indeed as William of Malmsbury wrote: “No ship that ever sailed England brought such tragic aftermath”.