On 22 August 1485, the course of English history took an unexpected direction.

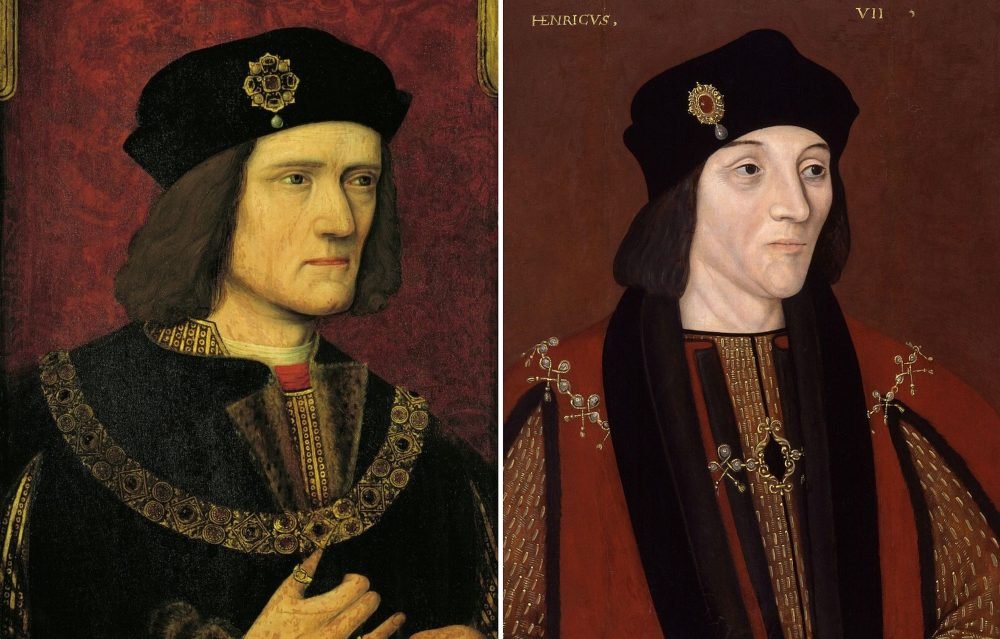

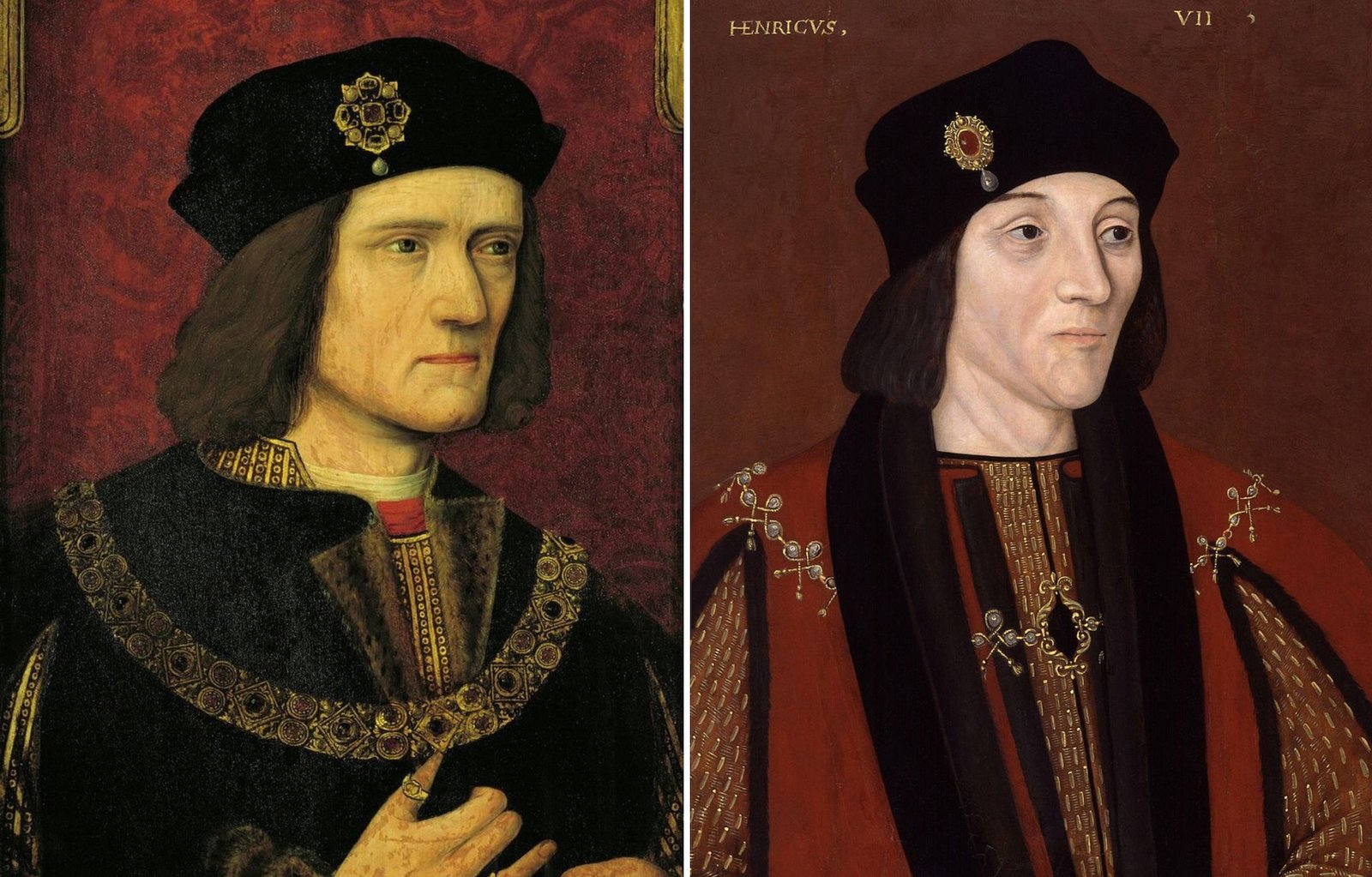

Two armies clashed on marshy open ground near Leicester, in a bitter fight that lasted around two to three hours. One man – among many hundreds of others – lay dead, and another received his crown in victory. Those men were Richard III and Henry VII.

This pivotal moment set a course of events in place that led to the break with Rome, the defeat of the Spanish Armada, union of the Crown between England and Scotland .

The Wars of the Roses: England in turmoil

The Battle of Bosworth cannot be understood without the Wars of the Roses. These dynastic struggles raged in England from 1455, as two rival branches of the Plantagenet family – Lancaster (represented by the red rose) and York (the white rose) – fought for the crown.

The Lancastrians were descended from John of Gaunt, a son of Edward III, while the York branch came via his older brother, Lionel, Duke of Clarence. They both claimed legitimacy since they came from Edward III.

The conflict was sparked by the weak reign of Henry VI (part of the Lancaster line), whose bouts of mental illness and inability to rule effectively left a power vacuum. Combined with the huge territory losses England suffered following the Hundred Years’ War and financial strains, tensions grew and the incapacitated (as well as conflict-averse) Henry was an easy target for others who claimed legitimacy and wanted a different direction for the country.

Edward IV deposed Henry VI in 1461, at the bloody Battle of Towton, and ruled until his death in 1483, with a brief six month hiatus with Henry VI back as King October 1470–April 1471. A skilled military leader, Edward oversaw many skirmishes and battles, and even betrayal from his younger brother George, retaining his position and power.

When he died, his brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, saw an opportunity and declared Edward’s sons illegitimate, taking the throne as Richard III. Suspicion surrounded Richard’s seizure of power, especially after the disappearance of the young Edward V and his brother in the Tower of London.

Discontent with Richard’s rule created an opportunity for other claimants, including Henry Tudor.

Henry Tudor’s claim to the throne

Henry Tudor’s blood claim to the throne was not especially strong.

On his mother’s side, he descended from Margaret Beaufort, great-granddaughter of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster and son of Edward III. But the Beaufort line had been born illegitimate, via a mistress; it was later legitimised but it still led to aspersions being cast on his right to rule.

On his father’s side, Henry was a Tudor – a family of Welsh gentry, cousins to Henry VI, who rose through loyal service to the Lancastrians.

What strengthened Henry’s position was politics: he was the senior claimant of the Red Rose after years of war had wiped out his rivals. Importantly, as part of his mother’s machinations while he was in exile on the continent, Henry also pledged to marry Elizabeth of York, eldest daughter of Edward IV.

This alliance would unite Lancaster and York, promising peace after decades of conflict.

Henry Tudor in Exile

Henry spent most of his youth in exile. After Edward IV regained the throne in 1471, Henry – then 14 – fled to Brittany with his uncle Jasper Tudor. For a further 14 years he lived under the protection of the Duke of Brittany.

Both Edward IV and Richard III attempted to have him handed over, even luring him with a promise of forgiveness and marriage.

During these years Henry grew into a cautious and patient figure, aware of his value as a figurehead for discontented Lancastrians. His mother, Margaret Beaufort, remained in England and plotted tirelessly to promote her son’s cause, forging alliances with nobles who had turned against Richard III – including with Edward IV’s widow, Elizabeth of York.

Preparing for the Battle of Bosworth

In 1483, when Richard seized the throne, Henry was the only real alternative.

A rebellion led by the Duke of Buckingham (known as the Buckingham rebellion) failed. But what it did do was strengthened the network of nobles ready to back Henry, seeing others willing to do the same.

With French support and financing thanks to Margaret of Anjou’s help, Henry – then 28 – gathered an army of around 5,000 men and sailed from Harfleur in August 1485, landing at Mill Bay, near Milford Haven, in Pembrokeshire on 7 August 1485.

From Wales, the Tudor army marched east, rallying supporters including Henry’s Welsh relatives and allies. By 12 August, Henry had won the support of the most influential landowner in south Wales, Rhys ap Thomas, who had been promised the Lieutenancy of Wales if Henry won.

His force remained outnumbered by Richard’s, with estimates ranging from 8,000-12,000 men on the King’s side. But the loyalty of key gentlemen and aristocrats (particularly Henry’s stepfather Lord Thomas Stanley and his brother Sir William) would prove decisive…

The battle begins on 22 August 1485

The armies finally clashed near Market Bosworth in Leicestershire, as Richard III had marched his men from Nottingham to meet the Tudor forces coming from the west.

Richard, 32, held the larger force and the high ground at Ambion Hill, while Henry’s men (now around 5,000 in number) advanced cautiously from their marshy, lower position.

Lord Stanley had held off calls from the King to rally his troops for as long as he could ahead of the battle – but did turn up in Leicestershire as requested, with around 4,000 men with his brother’s in total. This was in part due to Richard taking Thomas’ son, George, prisoner in order to guarantee his loyalty.

Thomas and Sir William Stanley lingered on the sidelines with their men, strategically waiting until they decided to intervene.

Henry’s men struggled uphill, losing many from their inferior position, but his Welsh bowmen were vital to inflicting serious damage to the other side.

At a critical moment, Richard spotted Henry moving across the field with only a small, separated bodyguard.

In a daring move, the King led a cavalry charge directly at his rival and into enemy lines, hoping to end the battle in one fell swoop. It was to be his undoing.

Richard came close: Henry’s standard bearer, William Brandon, who was positioned close to his leader, was killed in the targeted attack. But the Stanleys saw Henry’s weakness and intervened, surrounding Richard and his men.

Richard fought bravely in the two to three hours of fighting, reportedly refusing to retreat, but was cut down in the melee: a blow from a halberd at the bottom of his skull was the fatal injury, reportedly obtained while Richard’s horse was stuck in the marshy ground.

Richard III was the last English King to die in battle. His body had been thought lost for centuries until it was discovered in 2012 under a council carpark in Leicester – what once was Greyfriars Church – and confirmed to be the King the following year.

Richard’s crown was taken and placed on Henry’s head, by none other than Thomas Stanley, his stepfather.

The Tudor dynasty was born.

It is highly likely the Stanley brothers were in contact with Henry Tudor before he landed in Wales, and given Thomas’ family connection to the challenger, it seems he may have been willing to risk all for his stepson as a safer bet than the current King, whose popularity was declining…

But they were the deciding force at the Battle of Bosworth, showing how history can often rest on the acts of individuals.

After Bosworth

The Battle of Bosworth was final battle of the Wars of the Roses. It was not just the end of a conflict, but the start of a new era that reshaped the monarchy, the state, and England’s place in the world.

Henry Tudor became Henry VII, founding a new dynasty – one that would lead England for over a century. His marriage to Elizabeth of York symbolically united the red and white roses, creating the Tudor rose in both colours as a new national emblem; it represented unity and lineage.

Henry VII faced a number of challengers to his reign in the early years, such as Lambert Simnel, and Perkin Warbeck, who claimed to be the younger Prince in the Tower, Richard Duke of York.