It was a story that went around the world, astonishing history fans. Impossible as it might have seemed, the Richard III dig had found human remains beneath a Leicester car park – and it was indeed Richard III.

The remains had been found in the summer of 2012 but the project team confirmed on this day in 2013, that DNA had matched the King’s traceable descendants. Let’s take a look at how this story developed…

What happened to Richard III?

Richard III, the last Yorkist King and ruler of the Plantagenet dynasty, was killed on 22nd August 1485 at the Battle of Bosworth Field. This battle was the last major action of the Wars of the Roses, seeing Henry VII take the Crown and usher in the Tudor dynasty, and a new era of English history.

The Wars of the Roses, a series of civil wars between the Lancastrian Henry VI and Yorkists, led mostly during this conflict by Edward IV, had raged for decades, seeing King replace King by force three times.

Richard had usurped the throne from his nephew, Edward V, one of the famous Princes in the Tower, and challenges to Yorkist authority continued.

On the fateful day, Richard intercepted Henry Tudor and his men on their march to London, just south of Bosworth Market in Leicestershire. The two armies met at Bosworth Field and battle ensued.

Yorkist men outnumbered the Tudor force by nearly double, but the turncoat Thomas, Lord Stanley and his brother, Sir William Stanley, changed the battle’s direction. Initially staying clear of the fray with their men, raised on the King’s behalf begrudgingly, they chose to back Henry Tudor. It is worth noting that Thomas Stanley was Henry’s stepfather, married to the indomitable Margaret Beaufort, but was also a steward of the royal household under Richard III, and had bore the great mace at his coronation in 1483.

Richard, 32, had led a cavalry charge, and was slain whilst on horseback, ‘fighting manfully in the thickest press of his enemies’, reported Polydore Vergil, Henry VII’s official historian. Burgundian chronicler, Jean Molinet, however wrote the fatal blow came from a Welshman with a halberd – a long, axe-like weapon – as the King’s horse was stuck in the marshy ground.

His naked body was taken to Leicester, where it was buried in a crude grave in Greyfriars Church three days later, although another, later, erroneous account stated the King’s bones had been exhumed and disposed of in the River Soar at the nearby Bow Bridge.

The location of his burial was marked with a marble monument, destroyed during the Dissolution of the Monastaries under Henry VIII, and then lost to history as development in the city continued.

Richard III was the last King to die in battle.

Philipps Langley determined to find the King

The Richard III Society was founded in 1924 for those fascinated by the story of the missing King, and was originally known as The Fellowship of the White Boar. The group seeks to ‘secure a more balanced assessment of the king and to support research into his life and times’, and has around 3,500 members from the UK and abroad. Their patron is The Duke of Gloucester.

It was a mystery that had puzzled many historians of the period for decades – just where had Richard III been buried? The project sought to find the riyal remains and rebury his remains with the ‘honour, dignity and respect he was denied in August 1485’, the Society explains.

Research led Philippa Langley, a writer and member of the society, to believe that friary site was opposite St Martin’s church, now Leicester Cathedral, and not under what is now Grey Friars street as had been traditionally thought. That meant the Greyfriars site was in one of three car parks now used by council buildings.

Various attempts were made to dig at the proposed site over the years, including with the popular ‘Time Team’ archaeological programme, to no avail, and a survey of the ground with radar proved inconclusive in 2011.

Langley was determined to find the King’s resting place, and encouraged by her research, helped raise most of the funds needed to finance a dig (over £17,000 of the £32,000 total) from the society and its members, with the support of Leicester City Council and the University’s archaeological department.

Finally, with funding secured, the Looking for Richard project was underway.

The dig begins – and remains are found

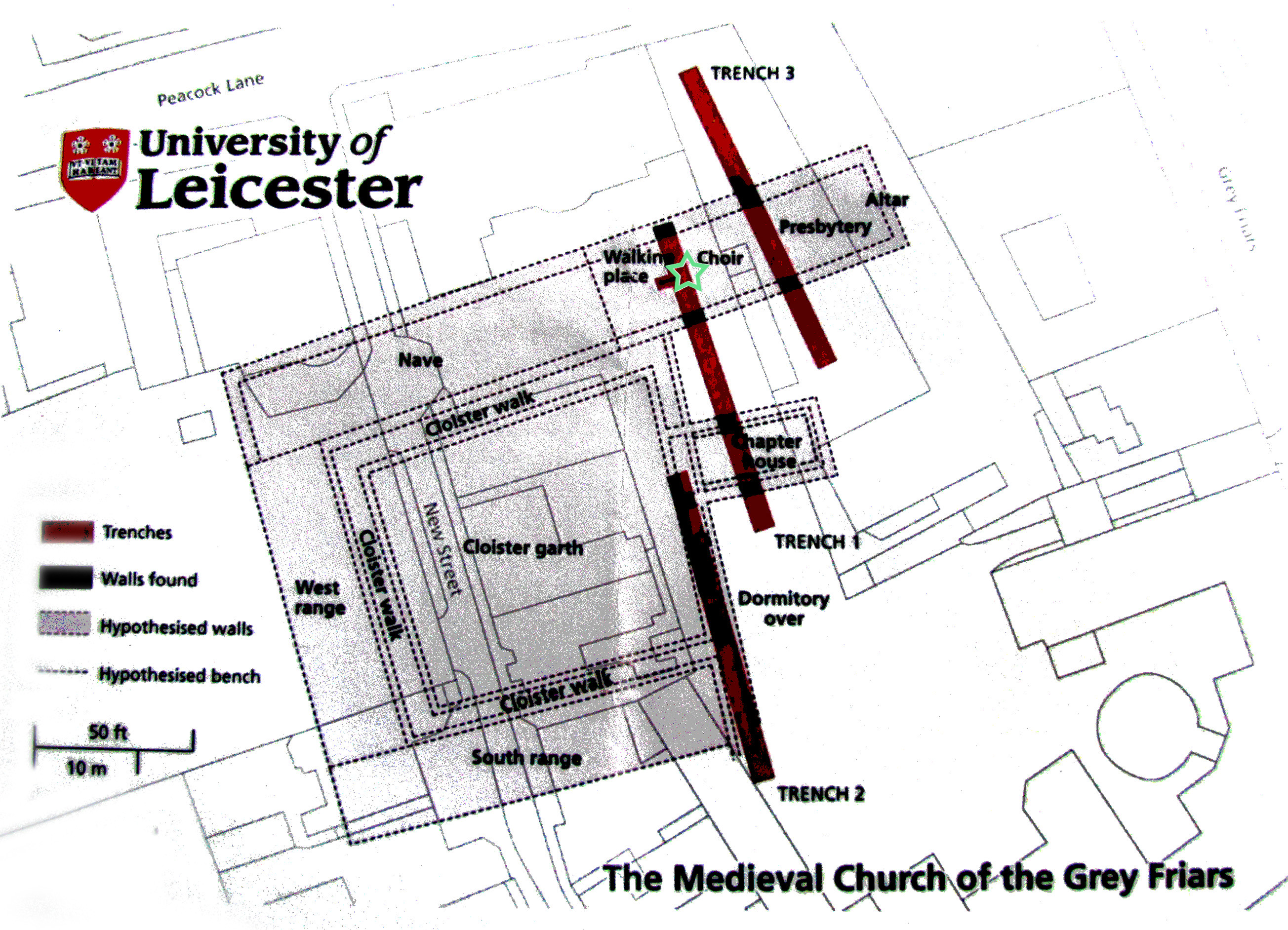

A two-week dig was agreed, to place three trenches on the car park site, starting with two. These would be place in a north-south direction to improve chances of excavating any potential walls of the church, which would run east to west.

And hopefully? The missing King.

Almost unbelievably, bones were found on Day 1 of the dig in the northern end of the car park, where Langley and renowned Richard III historian Dr John Ashdown-Hill concluded the choir of the church would be.

It was a leg bone, from the left leg of a male in his 30s – coincidentally discovered on 25th August 2012, the anniversary of Richard’s original burial. It was located about 1.5m from the surface, about six hours into the dig.

Philippa Langley observing the trench where a leg bone was found on the first day (Image courtesy of Richard III Society)

The church floor was found in another trench, but the team noticed the grave in Trench 1 was not a neat rectangle but a rough hole with untidy, sloping sides – this indicated it had probably been dug quickly and without great care. It was not long before they realised the grave was actually in the choir of what was once Greyfriars.

The crude grave where the male remains were found showed body had been positioned awkwardly, with the head propped up, since the space had been too short to lie the body down. The wrists were crossed, and had possibly been tied. There was no coffin or shroud, also indicative of a hasty burial.

From the beginning, it was clear the skull had been injured and that the spine was also curved, adding further intrigue.

Richard III’s remains were placed into a crude grave at Greyfriars, discovered more than 500 years later (University of Leicester/Flickr)

Philippa Langley at the grave site; the yellow pins show where the King’s head and feet were (Image courtesy of Richard III Society)

No further items were found in the trench with the remains.

Other graves were found, but these were dated to much earlier that the period of interest, and so were left unexcavated – especially since the first set of remains appeared to be very interesting.

Some of the Victorian brickwork was just 90mm above the skeleton: if workmen had dug further, the remains might have been damaged or even destroyed.

The remains had been found next to a parking bay labelled ‘R’…

Since the rules around human remains are quite strict, the team continued to excavate the remainder of the site before an exhumation order could be obtained a few days later.

Testing and DNA confirmation

The remains were carefully extracted, and then closely examined and scanned by experts, including carbon dating and forensic analysis using micro-CT.

Dr Jo Appleby, aided by Robert Woosnam-Savage, an expert in European edged weapons from the Royal Armouries in Leeds, helped identify that the remains were of the right age, with scoliosis and evidence of battle trauma – numerous indicators this could really be Richard III.

Further analysis of the skeleton showed the male had eight wounds to the skull, of battle-origin, and a further three wounds to the body. He had probably been killed either by a blow from a large bladed weapon, which had cut off the back of his skull, or by a sword that penetrated all the way through the brain.

There is evidence that some of these others were humiliation injuries, consistent with death in battle, and the wounds show that he was not wearing his helmet at the time. There was no withered arm, as legend had depicted.

While all signs seemed to point in the right direction, in order to be sure, DNA was extracted.

At a press conference in September 2012, the team urged caution but that there was ‘strong circumstantial evidence’ it was the Yorkist King, with the curved spine and injuries being ‘consistent’ with other accounts of Richard III.

‘There is strong circumstantial evidence [the remains are Richard III]. It is potentially a big find’, commented Richard Taylor, who led the search for the University of Leicester, at the press conference, but that they need ‘proper and rigorous testing’.

There was a chance that the DNA would have degraded, due to the conditions in the ground and centuries of time passing. Fortunately, this was not the case.

With DNA secured from the teeth, a mitochondrial match needed to be found to identify the King accurately, meaning the DNA was from the female line – a more certain form of DNA match.

In 2005, Ashdown-Hill shared that he had traced an all-female line descendant of King Richard III to Joy Ibsen, in Canada, via the King’s older sister, Anne of York. However, Joy had died the same year, meaning her son, Michael, was the next descendant, a 17th-generation great-nephew of Richard III.

A DNA swab was taken from Ibsen, as well as second, more-distant relative, and tested against that of the teeth found beneath the car park. It was a match.

On 4th February 2013, a press conference was held where the team shared it had concluded beyond reasonable doubt that the skeleton was that of Richard III.

This meant the Looking for Richard project had succeeded, and found the missing King. The odds had been stacked against them, nine to one, thought one of the archaelogists.

The story of the excavation and investigation was shared with the public in a Channel 4 documentary, Richard III: The King in the Car Park, broadcast the same day.

Richard’s life and looks

While further research was done on the trenches to find out more about Greyfriars, the bones were properly cared for, while the trench of his discovery was preserved.

A facial reconstruction was also commissioned, using the skull to recreate what Richard III had looked like to his contemporaries. This was produced by Professor Caroline Wilkinson formerly of the University of Dundee and funded by the Richard III Society.

The DNA suggested the King had a 96% probability of having blue eyes and a 77% probability of having blond hair (at least in childhood) like his brother Edward IV, but both of the earliest portraits of Richard, dated after his death, showed him with darker hair.

Embed from Getty Images

Michael Ibsen with his ancestor, Richard III

Embed from Getty Images

Richard III Society Chairman Dr Phil Stone and Philippa Langley with the recreation of the King’s face

The bust is on display in the King Richard III Visitor Centre in Leicester, just next to where the King was discovered, which opened in 2014. It includes a viewing section to the grave beneath the once-car park to where Richard was found.

DNA also allowed the team to understand more about his lifestyle. He had a mixed, protein-rich diet, probably 75% meat and 25% fish, typical of a wealthy nobleman of the period. His later life, shown by DNA from the ribs, indicates an increase in feasting and imported wine, likely aligning with his new role as King altering his lifestyle.

Microscopic egg casings were present, telling us that Richard III was infected with roundworm, which is spread through human faeces.

There is also indication of where Richard had been living in his bones; he likely moved out of eastern England, where he was born, by the age of seven or eight, but returned in his teens. This is consistent with historical evidence that he spent his early childhood at Fotheringhay, Northamptonshire, then time at Ludlow Castle in the Welsh Marches for a period in 1459.

The Leicester team shared this new information in August 2014.

The reburial

The King was reinterred on 26th March 2015 at Leicester Cathedral, with a funeral procession that took him from Bosworth – the place of his death – to the cathedral a few days before.

The location of his burial was subject to legal contention, with York Minster being offered as an alternative but Leicester won out.

White roses were placed by many, a nod to the Yorkist lineage of the King, during the procession, which saw thousands line the route. Many also queued the four hours to pay their respects inside the cathedral, where the coffin, topped with a recreated medieval crown and draped in a specially-embroidered pall, was at rest.

The coffin was touchingly made by his descendant, Michael Ibsen, from English oak from the Duchy of Cornwall. Ibsen is a carpenter by trade.

A rosary, donated by Ashdown-Hill, was blessed at the Clare Priory in Suffolk, reflecting Richard’s Catholic faith and placed in his coffin. The Priory is connected to Richard’s mother, Cecily Neville.

The service of interment was led by the Archbishop of Canterbury and televised, with The Countess of Wessex, Duke of Gloucester (patron of the Richard III society) and celebrities, including Benedict Cumberbatch – a descendant of Richard’s – in attendance.

His resting place is marked with a stone slab on a marble, decorated with a coat of arms and his engraved motto: ‘Loyaulte me lie’ – loyalty binds me.

Philippa Langley, who led the search for Richard III, said: ‘On the 10th anniversary of the identification of the King, I cannot thank the members of the Richard III Society enough for saving the search.

‘Without you the dig, and discovery, would not have been possible. With your financial support you gave the Looking For Richard project its mandate – “search-find-honour”. We have fulfilled that mandate.’