The image of Queen Victoria we conjure up is one of a widow, perpetually in black as she continued to mourn the death of her beloved Prince Albert.

But Channel 4’s documentary ‘Queen Victoria: Secret Marriage, Secret Child?‘ casts doubt on this image, and provides evidence that perhaps the Queen and her Highland servant were more than just companions…

For the century or so since Victoria’s death, people have speculated about John Brown’s role in her life. A privileged servant? Confidant and friend? …Lover? But no proof has ever been able to demonstrate this was more than simply a rumour. This is my review of the programme and its evidence.

★★★☆☆

3.5 / 5

This feels like confirmation of a romantic relationship, rewriting our understanding of Victoria’s widowhood – but a child? It’s a bridge too far with the evidence we have…

Queen Victoria: Secret Marriage, Secret Child?

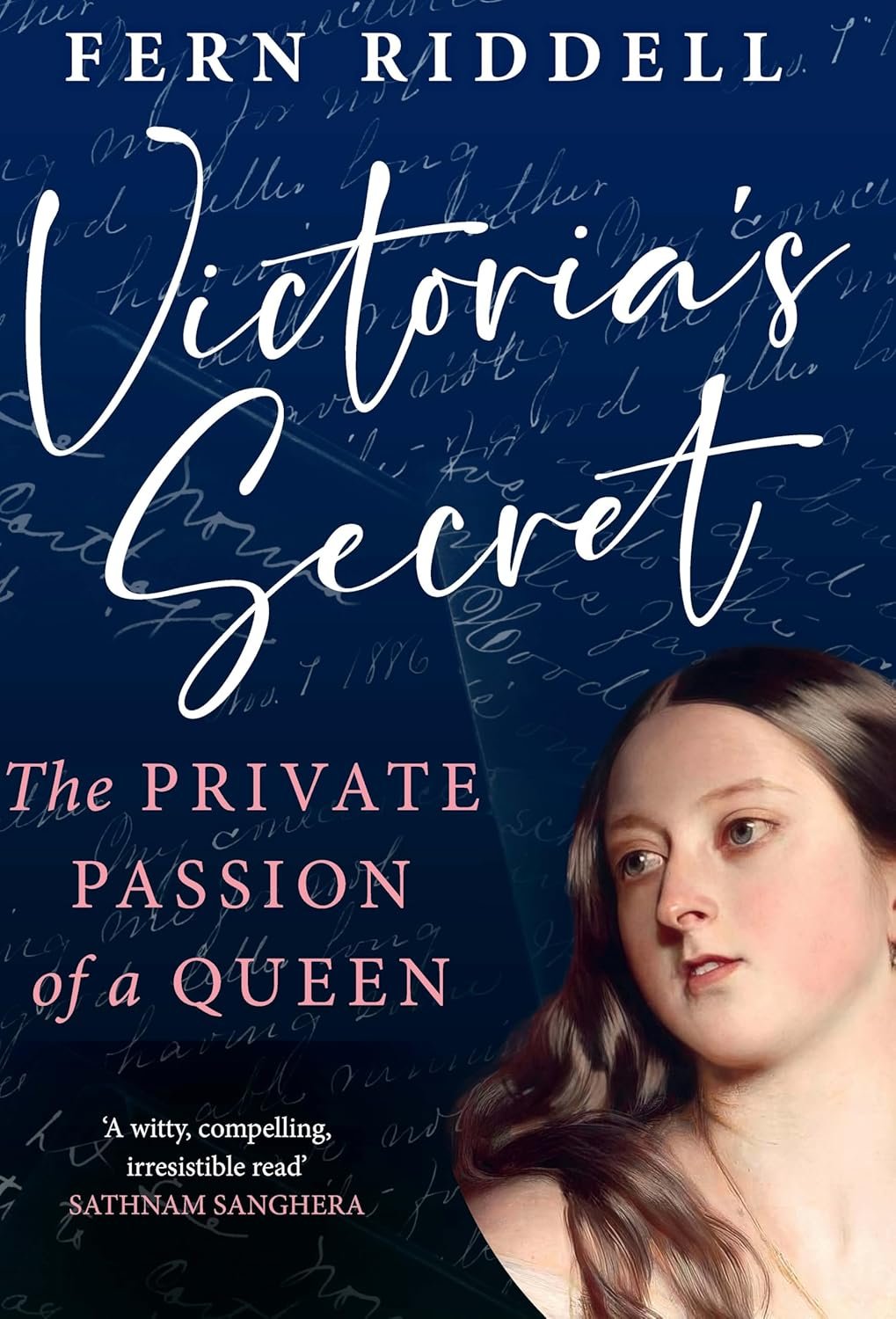

aired in the UK on Thursday 31 July, and brings together historian Dr. Fern Ridell and lawyer and legal TV personality Rob Rinder. It aired the same day as Riddell’s new book was released, ‘Victoria’s Secret: a Private passion of a Queen’.

Who was John Brown?

John Brown was a ghillie, or Scottish servant, to Queen Victoria. He grew up close to Balmoral, the gothic-style castle she and Prince Albert built in Aberdeenshire, having worked as a stable boy there before the Royals bought the estate.

He was initially an outdoors servant, taking the Queen rowing and riding through the countryside, especially when her husband was off shooting or on other pursuits.

By 1851, on Prince Albert’s orders, John Brown became the leader of Queen Victoria’s pony, and seven years later, John Brown became personal ghillie to the Prince Consort, showing how he had grown in esteem with both halves of the couple.

How did John Brown become so close to the Queen?

, John took on a more companion role. In December 1864, while the Queen was still deep in mourning, her family tried to pull her out of the deep pit of grief in order to not only fulfil her duties, but give her back some glimmer of enjoyment.

They suggested John Brown be brought down from Aberdeenshire to help her enjoy pony or cart rides, as she used to, which the Queen agreed to.

The Scotsman therefore entered permanent service to Victoria becoming ‘indefatigable in his attendance and care’, she wrote in her journal. This closer role saw him spend lots of time with the Queen and become one of her closest aides – much to the chagrin of other staff and her children.

Given this close relationship, there have been rumours for over a century about the true nature of their time together…

What evidence is there for a romantic relationship with Queen Victoria?

Dr Riddell shows us multiple pieces of evidence that indicate John Brown was likely more than just a close servant to Queen Victoria. To me, we can confidently believe that the Monarch cared very deeply for John (which was likely reciprocated) and that they were romantically involved – perhaps even lovers.

We see a number of heartfelt Christmas cards from the Queen to the ghillie. One shows a short verse that reads ‘I have loved thee with an everlasting love’, which is not everyday friendship language.

The Queen also insisted his rooms were put next to hers, wherever they went.

At John’s unexpected death in 1883, the griefstricken Queen writes of the loss of her ‘dearest best friend’. She also wrote to John’s brother, recounting a conversation between them. The handwriting, which does look like the Monarch’s, says: ‘Afterwards I told him no one loved him more than I did … and he answered “nor you – than me. No one loves you more.”‘

Additionally, two of her daughters, Helena and Louise, openly called him ‘Mamma’s lover’, which for years had been considered a joke or teasing nickname by historians.

A further sign of this long-standing deep affection was the commissioning of a cast of Brown’s hand, which Victoria also did for Prince Albert at his death. We are shown a photo of a large right hand wearing a signet ring and a cufflink bearing Victoria’s likeness.

The real cast is missing (with no reply from the Royal Collection as to whether they possess it the documentary shares) but the photo, from descendants of John Brown, proves its at least one-time existence.

The Queen also sent violets to the funeral, which in the popular Victorian language of flowers mean faithfulness and everlasting love.

When planning for her own death, the Monarch requested the following items be placed in her coffin alongside other family mementoes:

- a lock of Brown’s hair in her hand

- Brown’s mother’s wedding ring on her finger

- a photograph of him

- his handkerchief.

These, Riddell explains, were hidden in the coffin hastily before her children could see them or remove them.

However, that’s where the persuasion stops for me.

Did Victoria actually marry John Brown?

The evidence for this is difficult to take as more than speculation, but I would be open to the possibility of a secret marriage… We hear from a diary entry in 1885 that a Reverend Norman Macleod had confessed on his deathbed that he ‘bitterly regretted’ performing the ceremony between the Queen to John Brown.

This came from Lewis Harcourt, a 21-year-old future MP and son of the Home Secretary at the time, about Macleod who had been the Queen’s chaplain. The entry for 17 February is the one of interest. He writes:

‘Lady Ponsonby [the wife of the Queen’s private secretary and a lady-in-waiting] told the HS [the home secretary, Harcourt’s father] a few days ago that Miss Macleod declares that her brother, Norman Macleod, confessed to her on his death bed that he had married the Queen to John Brown, and added that he had always bitterly regretted it.

Miss Macleod could have had no object in inventing such a story, so that one is almost inclined to believe it, improbable and disgraceful as it sounds.’

This knowledge is recorded at at least third-hand (which Rob Rinder points out is multiple levels of hearsay in his legal opinion), and we are not really given Harcourt’s own take on the credibility of the story – he doesn’t say that he believes it, but almost.

I had to do some further digging to understand better, as this wasn’t on screen for long; I hope it is done in more detail in the book to critique its credibility.

As a source, it is unconvincing, not only given the lack of direct knowledge of this conversation. But a lack of further details giving the shocking nature of such a claim. When did it happen? Who were the wintesses? Why were there no follow up questions noted from the Home Secretary or the sister? Why has no one else from royal circles whispered that the couple were wed? And there is no family legend in the Macleod line relating to this, that made its way down a generation or two?

Secondly, we cannot rule out the possibility that Macleod did really say this – but that he may have simply been ill or delusional as he was shuffling off his mortal coil. It is simply irresponsible to put much store behind a third-hand conversation.

The other piece of evidence for the marriage we see is from a Swiss newspaper. The Gazette de Lausanne published the rumour in 1865 that Queen Victoria, then 46, was pregnant by her Highland servant and claimed she was secretly married to him.

Final points in the show highlight Victoria’s insistence that her children (all styled as HRH) were expected to shake Brown’s hand as if he were an equal. Odd, I grant you for a servant, but it indicates only that Victoria held Brown in high regard and wanted her family to do so too – not that they were married.

Riddell also suggests that a signet ring the Scot wore, which dates from 1872, may have been a sign of a morganatic marriage reflecting their wildly different ranks. But this reads deeply into a fairly popular piece of jewellery of the day.

Is there evidence Victoria had a secret child by John Brown?

We are presented with the fact that in 1865, a baby named Mary Ann was born. This child’s parents were on the birth certificate are listed as Hugh Brown, John’s brother, and his wife, Jessie.

Hugh and Jessie had left for New Zealand, where they bought a farm and registered the birth of their daugter. A little unusually, a letter from Victoria implores John to let her pay for the couple’s passage back to the UK.

If this were Victoria’s tenth child, she would have been an older mother – not impossible, but certainly a low chance, espesically as she piled on weight in her widowhood. Riddell thinks it was this extra weight that helped her conceal the pregnancy…

In 1874, the Monarch arranged for the small family to return to Scotland, giving them with a spacious home on the Balmoral estate – Riddell points out that some of Brown’s other siblings had bigger families but were not treated as well.

Another unusual twist to this tale is that the Queen commissioned a history of John Brown’s ancestry in

Dr Riddell tracked down this line to find Angela Webb-Milinkovich, who descends from Mary Ann Brown. Webb-Milinkovich, 47 and a native of Minnesota, explained that her family have held on to letters, jewellery and a lock of hair in a box of artefacts for generations, always having heard that there was ‘a big boat trip’ and ‘a baby given to the family’.

After John’s death, Victoria then relocated Hugh, Jessie and Mary Ann closer to her at Windsor.

Angela Webb-Milinkovich would like a DNA test to prove her lineage as a distant relative of King Charles III via her great-grandmother.

We do know that Victoria’s diaries were edited heavily on her instruction after she died, and her daughter Beatrice helped to destroy the originals, suggesting something truly was being hidden. But a child is a bridge too far for me, with this set of evidence.

Dr Riddell’s book is available to buy here.

Featured image: Lisby via Flickr / CC