Hardwick Hall is one of the finest examples of Elizabethan architecture in England.

Located in Derbyshire, its silhouette is instantly recognisable – even when speeding down the M1 – by its huge mullioned windows and the ‘ES’ monograms atop the towers.

These remind every visitor, and passer by exactly who was in charge in these parts: Elizabeth Talbot, Countess of Shrewsbury, better known as Bess of Hardwick.

The Hall stands proudly today next to the ruin of Hardwick Old Hall, testimony to Bess’ power, status and her shrewd nature, and offers the chance to understand influence beyond court life in London.

Bess of Hardwick’s childhood

In order to understand more about Hardwick Hall, we need to take a look at Bess’ life, and get at the root of her relentless ambition.

Born the daughter of a minor gentleman of Derbyshire, Elizabeth (‘Bess’) was likely born in 1527, on the site of Hardwick Old Hall, located near Chesterfield in the east Midlands. It seems that the land of Hardwick was passed down through generations of her family.

She was the youngest of five: three sisters and one brother. Her father died when she was just one year old, in 1528, leaving her brother – just two at the time – to inherit his estate of around 600 acres, 500 of them being in Hardwick and its surrounds.

James’ wardship was sold by Henry VIII, taking most of the family income away. Her mother, Elizabeth remarried, to a Ralph Leche.

He accrued debts that he could not pay seeing him spend time in the Fleet prison, with Elizabeth suing him for desertion soon after. Bess had clearly seen strong women in her life, and what the wrong choice of husband could do…

She had written how her mother was ‘very poor and not able to relieve herself[,] much less’ Bess or her other daughters. That is how the young Bess of Hardwick entered service for a time in London, working in the household of Sir John Zouche, a local Derbyshire gentleman, which gave her some of the necessary skills for a lady of the era: dancing, sewing, and music.

Widowed first at the age of 16, Bess married a total of four times before she was 41:

- first, Robert Barley, a minor landowner in Derbyshire and a cousin

- Sir William Cavendish, who made his fortune through Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries; together they purchased Chatsworth in 1549

- Sir William St Loe, Captain of Elizabeth I’s Personal Guard, which took Bess to the royal court

- George Talbot, head of one of the wealthiest families in England and later Earl of Shrewsbury, a Knight of the Garter and Privy Councillor to Elizabeth I, which significantly raised Bess’ social standing and wealth.

By the time she began building the New Hardwick Hall in 1590, Bess was a widow once more, a formidable businesswoman, with a taste for designing her homes.

Bess bought her family’s home of Hardwick from her brother in 1583, as one of his principle creditors.

The Earl and Countess had a strained marriage as time went on. This was mostly due to their responsibility for guarding Mary, Queen of Scots, which took its toll, and Talbot took armed guards to remove his wife from Chatsworth, which had been left to her by William Cavendish. Bess fled for the familiar safety of Hardwick.

Hardwick Old Hall

It was something of a higgeldy-piggeldy arrangement at the Old Hall, her childhood home, as Bess added rooms as and when she had the money; although Elizabeth was rich, most of her money was tied up in assets.

The Forest Great Chamber was painted to rival rooms at Theobalds, William Cecils’s home, and indicate that her decorative plans were linked to most of the popular trends of the time.

Plasterwork in this room showed scenes of near-life size humans and animals in the forest, which wends its way around the room, each section showing ‘sloping lawns with trees that recede into distance’.

Plasterwork in this room showed scenes of near-life size humans and animals in the forest, which wends its way around the room, each section showing ‘sloping lawns with trees that recede into distance’.

Elements of this can still be seen in the ruins today.

Building Hardwick Hall

Now in her 60s, and with four husbands behind her, Bess’ widowhood gave her even more financial stability, and meant the dream of a new home at Hardwick could be realised.

Positioning the new house just yards from the old, the location put the manor on a windswept hill above the valley of the River Doe Lea, to dominate the landscape.

The Countess wanted the rooms to get bigger as you progressed up the house, the reverse of the traditional style. She said this reflected the proper order of society, so that the state rooms, those for any important guests, would be at the top of the house, and the servants at the bottom.

Architect Robert Smythson thought her design a bad idea, but drew up a plan for the house. Bess made her alterations, and she was likely the driving force behind the project, giving detailed instructions.

Hardwick Hall is one of the earliest surviving examples in Britain of a building influenced by the Italian architect Andrea Palladio who create the Palladian style.

Its warm cream colour comes from limestone, which was quarried from the hills on which it sits, and you cannot fail to notice the windows. ‘Hardwick Hall, more glass than wall’ is a common saying about the property, thanks to its 156 windows – 30 of which are blind. Symmetry in Elizabethan architecture was important, so some of the windows are actually built in front of walls! It makes them a boast of wealth and status from Bess, along with the 35 fireplaces.

Oddly enough, the new house – though built to Bess’ design – was never large enough for her household of at least 82 people in 1596: staff and guests were usually accommodated in the Old Hall!

Layout

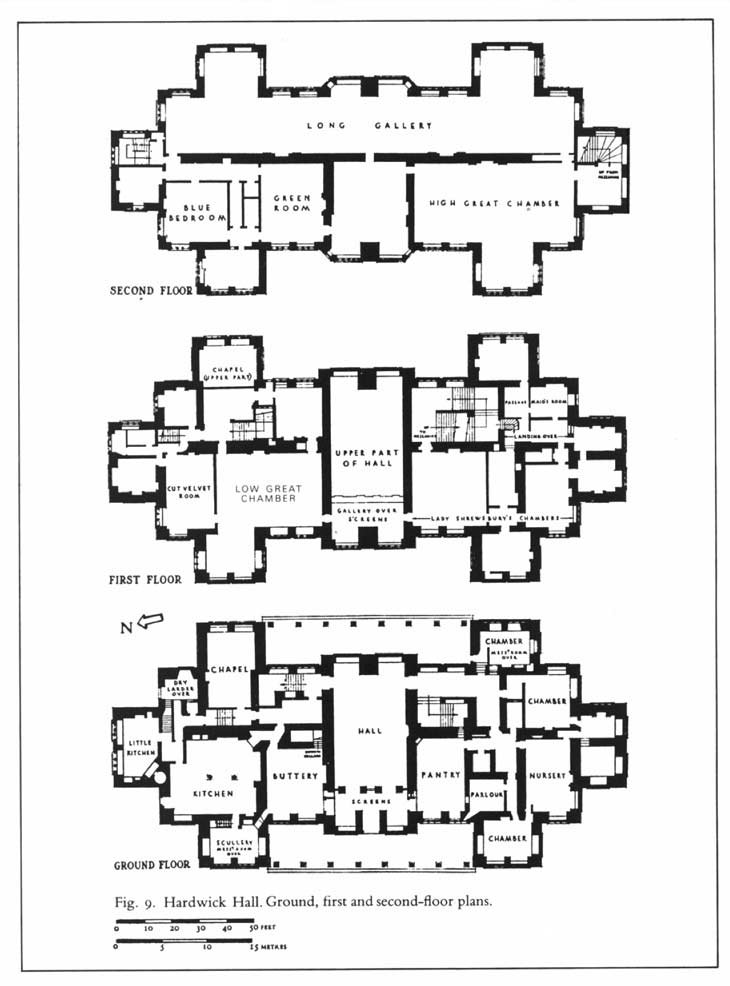

The outline of the house is a doubled greek cross. There are six towers, each of which are topped with the initials ES and a Countess’ coronet, and feature ‘banqueting houses’ at the top.

The ground floor was the focus of the domestic side of the house, including the Great Hall – a ‘radical departure’ from typical building design, positioning it at the centre of the house, straight off the front door, rather than at a right angle to the entrance; it takes influence from Palladio.

Other rooms included service rooms such as the pantry and butter, as well as the nursery.

On the first floor came the private rooms, where Bess had her own suite and where her granddaughter Arbella Stuart also lived, when being raised there, as well as the less grand, but still imposing Low Great Chamber.

The top floor was for guests, and entertaining, including the Long Gallery, the best bedchamber, the Great High Chamber and access to the towers.

Ground floor – the domestic space

Hardwick’s Great Hall

This hall was used by lower servants for eating, recognising the status shift to spaces upstairs.

Its double windows on both the east and west side would have made it a bright space most of the day, and it was the most elaborate room of this floor, given its function as an impressive entrance, though fairly sparsely furnished.

The focal point would have been the fireplace and its overmantel, featuring stags from the Hardwick arms with the Countess’ coronet: it was clear whose house this was to anyone who entered.

The feature also includes eglantine, or sweet briar roses, which were a sign of Elizabeth I’s purity and a nod to Bess’ friend, whom she was expecting to visit at some unknown point.

Such a visit never occurred.

Dynastic hopes

In both Bess’ withdrawing chamber and the Ship Chamber (also called the Cut Velvet Room) on the first floor, as well as various points throughout the house, we see signals of dynastic growth, hope and status.

The withdrawing chamber, where Bess spent most of her time, there are the Hardwick stags and the family’s latin motto, while the Ship Chamber displays the six coats of arms for her children, telling us about Bess’ hopes for her children’s successful marriages and status (much of which had already been secured).

Guests who used the Ship Chamber would have been equal to Bess’ own status as a Countess or lower ranking.

The Low Great Chamber was another dining room, and features a religious motto above the fire place: ‘the conclusion of all things is to fear God and keep his commandments’.

The room was adjacent to Bess’ apartments and probably was used by her as a dining and sitting room for herself, her ladies and Arbella. It was a display of piety, and demonstrated her role in educating her children and grandchildren – to be god fearing.

Second floor and state rooms

The state rooms on this floor were designed to mimic the Palaces of Richmond and Whitehall. They also had great views of the countryside – the land owned by Bess and her family.

Long Gallery

On the second floor we find a typical feature of Elizabethan houses: the Long Gallery. It runs most of the length of the Hall at 61m long and is the second longest in the UK (after Montacute). It was used for exercise, the reception of visitors, and the display of pictures, of which many hang on the walls.

Two fireplaces are surmounted by statues of Justice and Mercy, while a tapestry of Gideon and the Midianities – bought by Bess in 1592 – is hung. She paid the handsome price of

£326 for a set of 13 panels; it is the largest tapestry set to survive in Britain today and recently underwent a 24-year conservation project.

Bess even had £5 deducted from the price because she had to change the previous owner’s coat of arms to her own…!

There were no curtains mentioned in inventories for the gallery, meaning it would have been an airy space, especially with larger height ceilings being on the top floor, and the south window, positioned so that it got the low winter sun even in the cold months.

Green Velvet Room

This is the ‘best bedchamber’ and was where the Queen would have stayed, had she ever made it to Derbyshire. The fireplace and doorframe are carved and inlaid Derbyshire alabaster, blackstone and other marbles.

The room acts as testament to Bess’ fidelity and the triumph over the Earl of Shrewsbury and their marital difficulties – stories which all guests would have known.

It lauds ‘female virtue and its fight against masculine weakness and excess’, with tapestries that depict the Virtues and their contraries, while others show the pagans Mohammed and Sardanapalus, and the traitor Judas.

Widows ‘were constantly prey to doubts about their social status, their sexual experience and their lack of male supervision’, so this was a deliberate move by Bess, giving her the final word.

High Great Chamber

A t-shaped space thanks to its deep bay window provided by one of the towers, you can see the Chair of State and dais, directly opposite the door in the High Great Chamber would have given an imposing welcome to those who entered… Guests would have had to walk the 20m depth of the room to reach the dais and greet such an important figure, all whilst surrounded by Bess’ homage to the Queen.

Decoration illustrated Diana and her maidens, and the royal coat of arms is placed over the fireplace, in a display of loyalty.

It is also the room with the most windows at Hardwick.

Guests were entertained here, and it functioned as a dining room, meaning food was brought up the main staircase to diners, cooling as it came.

An Elizabethan Time Capsule

One of the most remarkable things about Hardwick Hall is that it remains furnished much as Bess intended. In 1601, the Countess commissioned a complete inventory of her belongings for her will. This document, sometimes called an ‘Acre of Canvas’, allows us to know exactly which items sat in which rooms four centuries ago.

The Sea Dog and Eglantine Tables

The collection includes pieces of furniture that are internationally significant: the Sea Dog Table iand the Eglantine Table.

The Sea Dog Table is a marble-inlaid walnut masterpiece supported by chimeras, or ‘sea dogs’, resting on tortoises. Based on French designs, probably made in Paris, it is considered one of the most important pieces of 16th-century furniture in the country, that Mary Queen of Scots no doubt saw and admired, still proudly on display in the Withdrawing Chamber.

It is also the only piece of furniture currently at Hardwick which can be definitively identified in the inventory of 1601.

Equally rare is the Eglantine Table, which takes its name from the motto inlaid into its centre and for centuries has sat in the High Great Chamber.

The walnut top is intricately inlaid with fruitwood and limewood to depict musical scores, playing cards, and gaming boards. The heraldic and dynastic references strongly suggest that it was made to commemorate family marriages in 1567-1568.

Bess agreed to marry George Talbot in 1567, and also bargained the match of two of her children to two of his: her eldest son, Henry Cavendish, married Lady Grace Talbot, George’s youngest daughter, on 9th February 1568, while her second daughter Mary, married Gilbert Talbot, his second son (though their match is not included in this design).

Virtue in needlework

Hardwick is rightly famed for its textiles, which include some of the finest embroideries in the country.

The Noble Women series consists of four large appliqué wall hangings depicting strong female characters from the ancient world, such as Penelope and Lucretia, flanked by personifications of their virtues. These were likely created while Bess lived at Chatsworth in the 1570s and were moved to her private withdrawing chamber at Hardwick.

Interestingly, many of the hangings and embroideries in the house feature stitches from Mary, Queen of Scots, who spent years in the custody of the Shrewsburys. It appears the two got on well, as the Earl had to write to William Cecil, Elizabeth’s spymaster, to refute ‘suspicion… of over much good will born by my wife to this queen’.

A legacy to her ambitions

Bess moved in to her new, impressive home on 4th October 1597.

Interestingly, the Countess continued extending the Old Hall as she built her new home, and both projects continued parallel for many years.

Bess died in 1608, aged 80 or 81, leaving Hardwick to her son, William Cavendish, 1st Earl of Devonshire. For centuries, the house served as a home for the Dowager Duchesses of Devonshire, while the incumbent and their family stayed at Chatsworth; this meant that there was little money spent on the Hall, and is exactly why the hall remains such a perfect Elizabethan time capsule today.

The house was transferred to the National Trust in 1956 in lieu of death duties, while the Old Hall – now mostly ruinous – is managed by English Heritage.

Hardwick Hall, with its resolute ES monograms, Hardwick and wider family crests throughout, remains the ultimate monument to the woman who rose from a struggling orphan, to a Countess with the ear of the Queen.

And an ancestor of the longest-reigning Monarch: through the Dukes of Portland, Bess’ own blood runs into the Cavendish-Bentnick line, and the maternal grandmother of Elizabeth II.

Sources:

- French, Sara L. “Hardwick Hall: Building a Woman’s House.” In Bess of Hardwick: New Perspectives, edited by Lisa Hopkins, 121–41. Manchester University Press, 2019.

- French Sara, “A Widow Building in Elizabethan England: Bess of Hardwick at Hardwick Hall.” In Widowhood and Visual Culture in Early Modern Europe, edited by Allison Levy, 161-176. Routledge, 2003.

- Friedman, Alice. 1995. Hardwick hall. History Today. 01, https://www.proquest.com/magazines/hardwick-hall/docview/202811380/se-2 (accessed February 13, 2026).

-

Dean Hawkes & Ranald Lawrence (2021) Climate, comfort, and architecture in Elizabethan England: an environmental study of Hardwick Hall, The Journal of Architecture, 26:6, 861-892, DOI: 10.1080/13602365.2021.1962389

- National Trust, Hardwick, https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/visit/peak-district-derbyshire/hardwick