The Restoration and reign of Charles II are both notorious for their associations with excess: gambling, drinking and of course, women and sex. This series of posts will explore Charles II’s mistresses, including Barbara Villiers, Nell Gwynn, and Louise de Kerouaille.

On May 30th 1660, King Charles II re-entered London, bringing 11 years of experimental republican government to a close. He had been in exile intermittently since the execution of his father in 1649, hunted by enemies of his dynasty while England was ruled by the puritanical, Cromwellian government. It had been a time of constitutional ferment, but also moral restriction, dancing, card playing and even Christmas were forbidden, while Oliver Cromwell himself had led a life of impeccable monogamy and religious observance. With the return of Charles II, the so called ‘Merrie Monarch’, all of this came to an abrupt end.

Barbara Villiers, Duchess of Cleveland. REMIGIUS VAN LEEMPUT

The Interregnum had been a revolution, and the end of that revolution brought out extremes in all walks of English – as well as British – life. It has been written that “the pendulum [of England’s morality] swung from repression to license more or less overnight,” said Roger Baker in 1994, and to some extent this holds true. While former Parliamentarians fell into despair at the failure of their austere ideals, many other parts of society took the opportunity to cut loose and throw an exuberant party.

The Restoration age saw a flowering of the arts and liberality. In architecture, Sir Christopher Wren designed a magnificent new St Paul’s after the Great Fire of London. In literature, the Earl of Rochester shocked people with his outrageously sexual verse, Samuel Pepys kept his meticulous diary and John Dryden was made England’s first poet laureate. This was also the age when Thomas Hobbes and John Locke wrote pioneering works of political science, which have shaped the world up to the present day. It was a flirtatious age of theatre, drama and change, with England emerging from the turmoil of the revolution and Interregnum with a new vigour and life.

Society and the reestablished royal court showed some of these same extreme reactions, helped along greatly by the personality of the 30-year-old King. In contrast to his pious father and Cromwell, Charles II had a passion for all the excesses in life. Even during his exile, Charles had developed a reputation as a womaniser, one that sometimes erred a little too far toward debauchery… Queen Anne was far from the first Stuart monarch to be accused of over reliance on ‘favourites’.

While he was immensely likeable personally, and a far more capable and flexible Monarch then his father, more than a few of Charles’ subjects began to worry that his natural inclination towards pleasure sometimes led to being distracted from the serious business of ruling, or allowed undue influence to be wielded by undesirable characters. Indeed, the ‘evil minister’ was a common character of the seventeenth century.

king charles ii – royal museums greenwich

Of all the King’s many famous mistresses or ‘favourites’, the first of his new reign has come down to us as possibly the most notorious and grasping of them all. Or was she? At such a distance of time is possible to tell the woman from the rumour? In other words, who was Barbara Palmer?

Barbara Palmer, The Duchess of Cleveland

“The curse of the nation”; John Evelyn

“I can never enough admire her beauty”; Samuel Pepys

“The finest woman of her age”, Sir John Reresby

Barbara Palmer, nee Villiers, was born in 1640 into the wealthy and noble Villiers family. The family had already provided one royal favourite in the form of Barbara’s great-uncle, George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham; he was James I’s favourite and suspected lover. Buckingham was widely hated; clouds of gossip, jealousy and scandal swirled around him (as would later swirl around Barbara) and his end came in the form of a disgruntled soldier that stabbed him 27 times. His great-niece would be much luckier.

Barbara Palmer, 1st Duchess of Cleveland, by John Michael Wright (1662). Wikimedia Commons

Barbara’s own branch of the family was considerably less well-endowed. Her father had been killed in the Civil Wars (1642-1648) while she was a child and during the republic the family had kept a low profile. During this time, Barbara grew into a natural beauty, as the countless surviving portraits of her attest: Peter Lely, Charles II’s court painter, is reputed to have exclaimed ‘she is beyond the power of art’. Nevertheless, he painted her many times. She was tall and voluptuous, with a mass of dark curly hair, heavy violet eyes and alabaster skin, a model which became the Restoration ideal of beauty and saw her style widely imitated.

Barbara’s sexual career began early, with an affair with Lord Chesterfield being widely recorded when she was only 15. Following this, she married Roger Palmer, a member of the gentry, as well as a Roman Catholic. He was a shy and retiring writer, hardly a good fit for one of the most famous libertines of the age: it was said his own father warned him he would become the most miserable man in England by marrying Barbara. However, the warning clearly had no effect, as the two married in 1659 and within the year, made the trip to Holland to visit the exiled Charles II, who was preparing for his triumphant return.

It is here that Charles and Barbara met and where their affair began. She was 20, he 29. Both had had lovers prior, and soon enough both would be married, but it’s clear they took to each other from the very first. While we don’t know exactly when the affair began, we know that on the day Charles II rode triumphantly through London in 1660, he appears to have ended that day in her bed. From then on, Barbara built her position into that of an uncrowned Queen.

We have a wealth of accounts of Barbara from courtiers of the time, not least from the famous diarist, Samuel Pepys, who just so happened to live next door to Barbara and her cuckolded husband Roger. At this stage, Barbara was not the almost universally disliked mistress-in-chief she became. Pepys seems to be rather taken with her beauty, happily recording in 1661: “I can never enough admire her beauty.” He also records her comings and goings often, as well as the King visiting her.

Samuel Pepys, by Godfrey Kneller, (1689). Wikimedia Commons

It appears he was not the only one. In the first five years of the new King’s reign, Barbara gave birth to a royal bastard every year: Anne, Charles, Henry, Charlotte and George (more on them later). She used her power and influence over the King to appoint Peter Lely as court painter in 1661, who repaid her a thousandfold with portrait after portrait (this was not nothing – by his death in 1680, Lely was charging £40 for a half-length portrait). Her beauty was praised to the skies and it is from these early years that the more positive quotes listed above are taken. In order for her to receive the treatment he felt was her due, Charles created her unfortunate husband Roger The Earl of Castlemaine, and afterwards Barbara herself was known as Countess (or Lady) Castlemaine, and treated with all the honour and dignity the title demanded.

Naturally having children with another man and spending so much time and energy on her affair with the King caused strains in Barbara’s marriage. Things came to a head, when in 1662, Roger insisted on Charles (the second child of Barbara and the King) being baptised into his own Catholic faith rather than the King’s, that of the Protestant Church of England. Barbara acquiesced, only to have the baby re-baptised a Protestant in the Charles II’s presence a few days later. Once Roger found out, several blazing rows ensued, the result of which was that he left London for France and never met Barbara again, effectively ending their marriage. The couple never formally separated, however, and were legally married until Roger’s death in 1705.

Lady Castlemaine was now free to devote herself entirely to retaining the King’s love and increasing intrigues at court.

Charles II married the Portuguese Princess, Catherine of Braganza, in 1661, and this conversely only strengthened Barbara’s powers and influence. Catherine was meek, plain and mild mannered – she had none of the vivacity and wit that Charles craved and Barbara provided. An unfortunate incident shortly after the wedding is probably what cemented Barbara’s position in the national psyche as ‘the curse of the nation’.

Charles II & Queen Catherine of Braganza, William Salmon.

Realising she would do well to have an official title at court and an income, Lady Castlemaine demanded that Charles make her his new wife’s chief lady of the bedchamber. The horrified Queen Catherine knew exactly who she was and struck Barbara’s name from the proposed list, when it came to choosing her household. The furious mistress went straight to Charles and berated him until he appointed Barbara anyway, overruling the Queen. As her new ladies in waiting were presented to Queen Catherine (who had never seen Barbara before), one of her Portuguese ladies whispered who Barbara was, whereupon the unfortunate Queen became extremely agitated and bled profusely from the nose, before fainting. She still refused to accept Barbara until Charles finally threatened to dismiss all of Catherine’s Portuguese retainers and leave her friendless in a foreign court if she did not comply. Finally, she gave in and accepted Barbara’s position. This dramatic slap down to his new bride (quite apart from the fact that Barbara had given birth to their second child during Catherine and Charles’ honeymoon) guaranteed Barbara’s position; she was now untouchable.

For the next few years Barbara reigned supreme. She squandered half a million pounds in gambling debts, which eventually led her to demolish the magnificent Nonsuch Palace to pay her creditors. She caused ladies-in-waiting and ministers of state to be dismissed and her power was feared by many. Even the once-admiring Pepys lamented of the King that ‘my lady Castlemaine rules him’, and disapproved of the factional bickering she promoted.

But her tenure was – not unexpectedly – short lived. Charles II was above all a restless lover, and it was inevitable he would find other mistresses:

‘Restless he rolls about from whore to whore,

a Merrie Monarch, scandalous and poor’, wrote the Earl of Rochester.

By 1663, the King was already infatuated with Lady Frances Stuart, and Barbara took this new mistress under her wing in an attempt to maintain her influence. This seems to have driven the competitive streak in Barbara wild; there are numerous stories from these years of Barbara wearing the most jewels and most extravagant dress of any lady in the court in an effort to retain attention. Despite sleeping with the King less and being increasingly unpopular for her extravagance, Barbara was still influential enough to see her greatest rival Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon (one of Charles II’s oldest friends and chief adviser) forced form power in 1667 after speaking out against his foreign policy. He was used as a scapegoat for the disaster of the Second Dutch War, which ended in defeat in 1665, with the humiliation of the main naval ship being towed away from its mooring uprive of the Thames by the Dutch. It was to be her last triumph: shortly thereafter her influence began to fade.

We do not know what exactly caused Barbara’s fall from grace, but her own promiscuity likely had something to do with it. Barbara had been even less faithful to Charles than he to her, and there are references to other lovers throughout her time at court. The issue came, when in 1672, she attempted to force Charles to acknowledge paternity of her latest child. When the King protested that he could not possibly be the child’s father as they had not slept together in months, Barbara threatened to dash the child’s brains out once it was born if he did not treat it as one of his own. The King dropped to his knees and begged Barbara’s forgiveness, which – while it secured this last child title and money – did her no favours. After this incident, she was gradually seen less and less at court. Despite loading her with honours and gifts, the King preferred the easier company of his new mistresses Louise De Keroulle and Nell Gwynn. Barbara was too controlling, too abusive and by now in her thirties, too old to capture his attentions.

She eventually moved to Paris in 1676, her position at court long eroded. She continued to take other lovers but she and the King remained distant friends, spending a pleasant evening reconciled to each other in the week before his death.

Barbara Palmer in old age, Godfrey Kneller (1705). Wikimedia Commons

Despite returning to England by 1680, in her later years Castlemaine returned to prominence once more. At the age of 63 she married a man 10 years her junior, who turned out to be a bigamist, only after her money. Needless to say Barbara swiftly divorced him and faded back into impoverished retirement. She finally passed away in 1709, likely from oedema (fluid retention) which disfigured her beauty by causing her to swell to enormous proportions. She was survived by five of her six children, all of whom were ennobled.

So what are we to make of this favourite, who alternately captivated and disgusted a nation? She was undoubtedly power hungry and grasping. Barbara’s – and Charles’ – treatment of poor Queen Catherine was certainly appalling. However, down the centuries we also have a picture of a beautiful and fierce woman who fought hard to seize and maintain her power over a King, who was notoriously difficult to keep entertained for long. I very much doubt Barbara would have cared what people thought of her: nothing recorded of her life shows a woman desperate for public adulation, and in some ways that his her most redeeming quality.

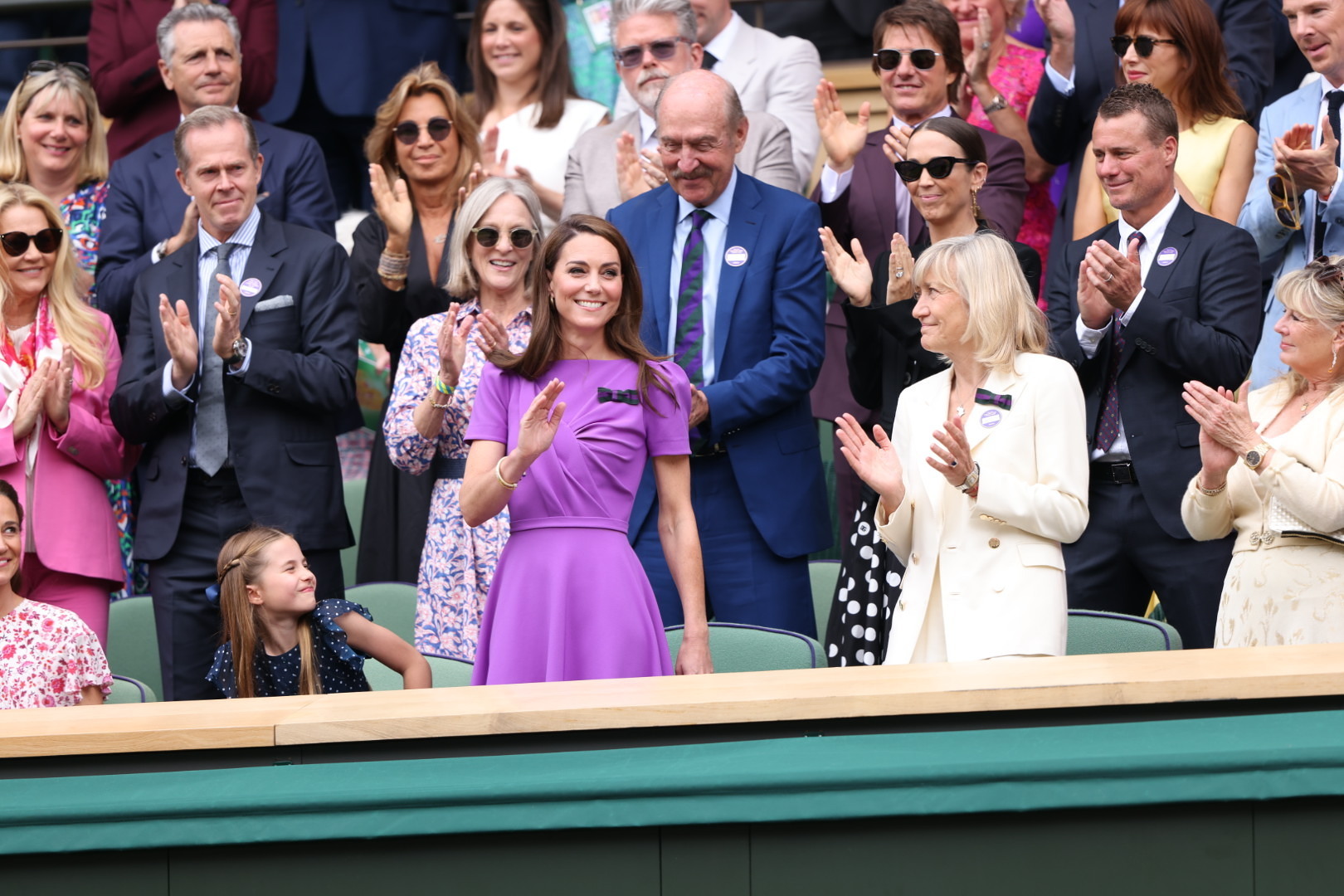

When he (eventually) becomes King, Prince William will hold the distinction of being the first direct descendant of Charles II to reign, and it is his connection to Barbara Palmer we have to thank for this. Barbara’s third child, Henry Fitzroy, 1st Duke of Grafton, was a direct ancestor of the late Diana, Princess of Wales, and so through William, Harry (and many others) the blood of Barbara lives on to this day. There is no doubt she would be immensely satisfied.